|

BLUEBIRD K7 and

DONALD CAMPBELL

|

||

|

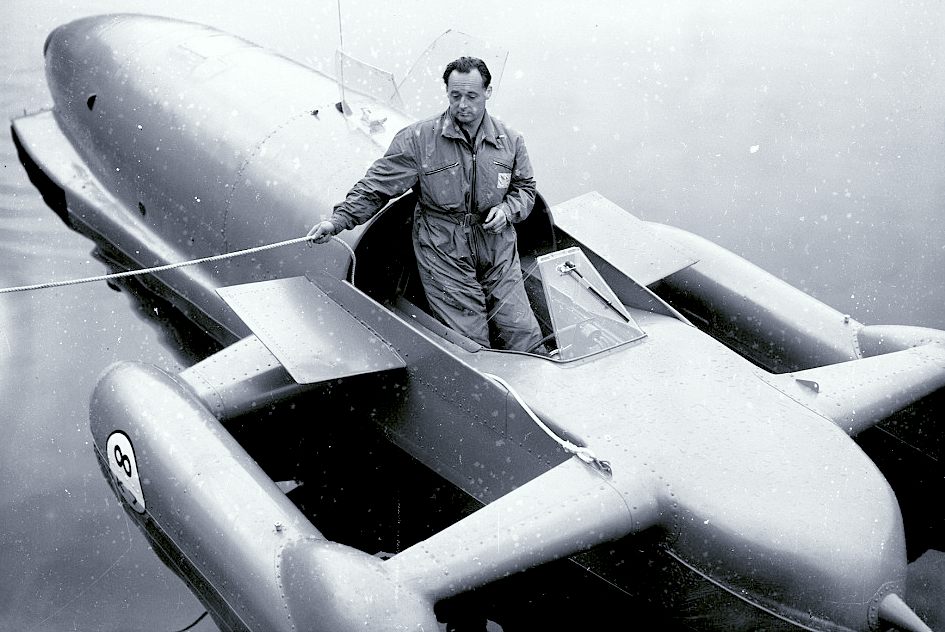

The K7 on Lake Coniston at high speed

The Bluebird K7 was and is a turbo jet-engined three-point hydroplane with which the United Kingdom's Donald Campbell set seven world water speed records during the 1950s and 1960s. She was though more than that, she became and remains an icon for man versus the elements, the extraordinary and a symbol of finality, warning us to tread carefully. Campbell lost his life in K7 on January 4, 1967 whilst making a bid to raise the speed record to over 300 miles per hour (480 km/h) on Coniston Water. A tragedy, but also a finale that raises the bar.

K7 Design

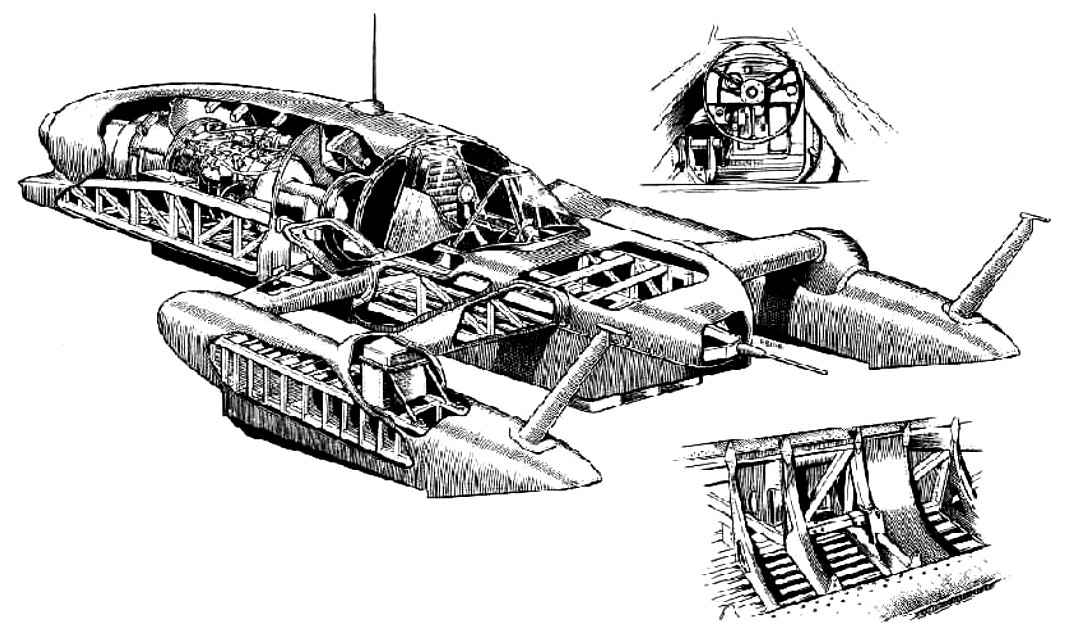

Like Slo-Mo-Shun, but unlike Cobb's tricycle Crusader, the three points were arranged in "pickle-fork" layout, prompting Bluebird's early comparison to a blue lobster. It was very advanced, and remained the only successful jet-boat until well into the 1960s.

The other vehicle that Donald Campbell was instrumental in creating, with the indispensable services of Ken and Lewis Norris: the CN7 jet powered LSR car.

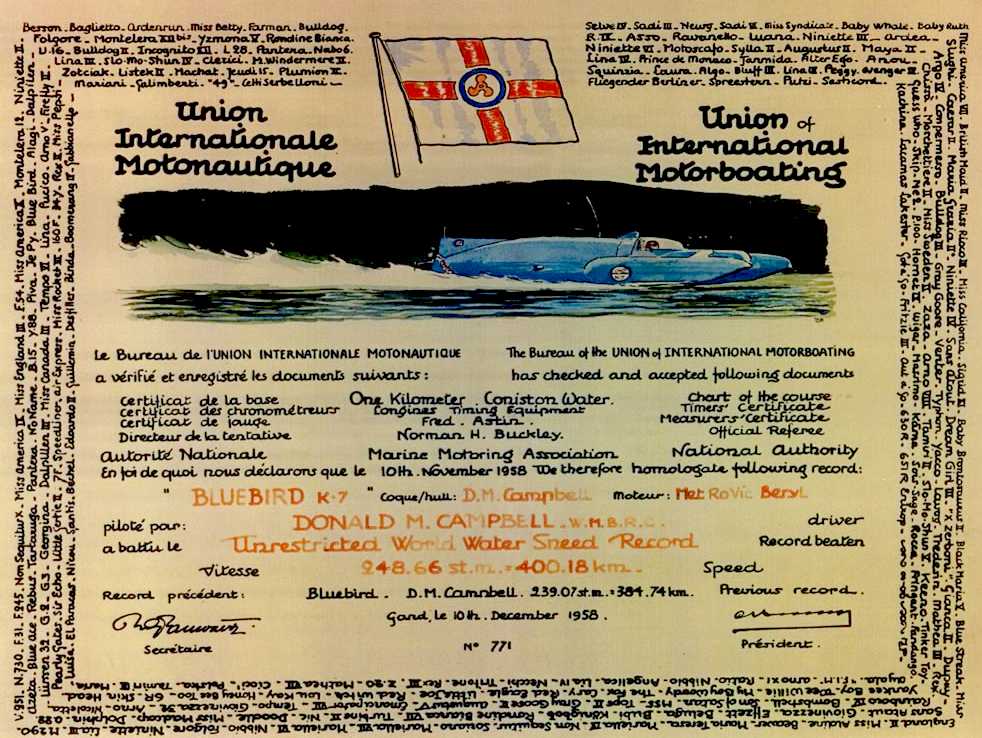

In order to extract more speed, and endow the boat with greater stability, in both pitch and yaw, K7 was subtly modified in the second half of the 1950s with the installation of smoother streamlining, a blown cockpit canopy and, from 1958 onwards, a small wedge shaped tail fin, modified sponson fairings, that reduced aerodynamic lift, and a fixed hydrodynamic fin, fixed to the transom to aid hydrodynamic stability, and exert a marginal downforce on the nose. Thus she reached 225 mph (362 km/h) in 1956, where an unprecedented peak speed of 286.78 mph (461.53 km/h) was achieved on one run, 239 mph (385 km/h) in 1957, 248 mph (399 km/h) in 1958 and 260 mph (420 km/h) in 1959.

Campbell then turned to the LSR, and after surviving a high speed crash in his Bluebird CN7 turbine powered car, he spent a frustrating two years in the Australian desert, battling adverse conditions. Finally, after Campbell exceeded the LSR on Lake Eyre in 1964, at 403.10 mph (648.73 km/h) in Bluebird CN7, Campbell snared his seventh water speed record on 31 December 1964 at Dumbleyung Lake, Western Australia, when he reached 276.33 mph (444.71 km/h), with two runs at 283.3 mph (455.9 km/h) and 269.3 mph (433.4 km/h) completed with only hours to spare on New Year's Eve 1964.

This made Campbell and K7 the world's most prolific breakers of the Water Speed Record, inspiring K777 and others to produce similar boats and models. Campbell became the only person to break both the Land Speed Record and the Water Speed Record in the same year.

Land transport is essential for small WSR boats. Here the K7 is being delivered to Goodwood on this small articulated truck. You can see from this picture where the name lobster came from.

K7 was fitted with a lighter and more powerful Bristol Siddeley Orpheus engine, taken from a Folland Gnat jet aircraft, and lent to the project by the MOD, which developed 4,500 pound-force (20 kN) of thrust. The new K7 had a vertical stabiliser (also from a Gnat Campbell had purchased ) and a new hydraulic water brake designed to slow the boat down on the five-mile Coniston course.The boat returned to Coniston for trials in November 1966. These did not go well; the weather was appalling and K7 destroyed her engine when the air intakes collapsed under the demands of the more powerful engine, and debris was drawn into the compressor blades. The engine was replaced, Campbell using the unit from the scrapped, crash-damaged Gnat aircraft that he had purchased at the project's start. The original engine remained outside the team's lakeside workshop for the rest of the project, shrouded in a tarpaulin.

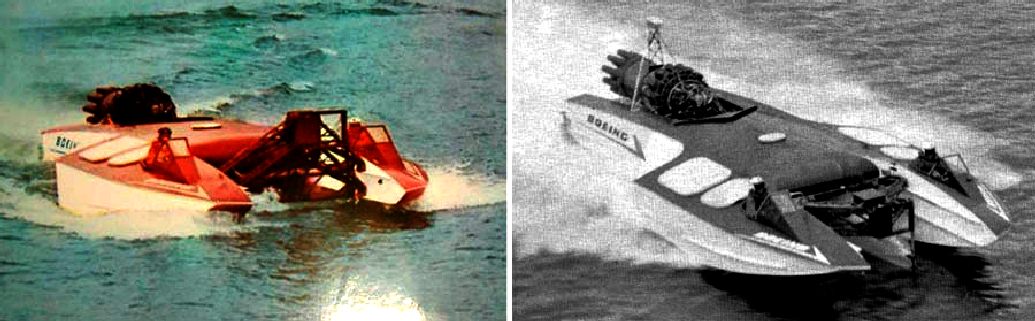

AQUAJET - Slow to catch on, the US Navy commissioned Boeing began their research and development of hydrofoils in 1959. The hydrodynamic test system (HTS), called the Boeing "Aqua-Jet," was launched in 1961 and closely followed the design configuration the Ken Norris pioneered several year before. The AquaJet was a dual-cockpit jet-powered hydroplane that served as an aquatic version of a wind tunnel. Powered by an Allison J-33 jet engine, the HTS was designed to provide a level and stable platform for straightaway runs of up to 132 knots (115 mph/185 kph). Boeing knew that this layout was safe at the speeds they were looking at because of the renowned stability of the K7 Bluebird at much higher speeds. The big difference was that unlike the K7 that was very nervous on rough water, the Boeing was more forgiving of a bit of chop.

By the end of November, after further modifications to alter K7's weight distribution, some high-speed runs were made, but these were timed at well below the existing record. Problems with the fuel system meant that the engine could not develop maximum power. By the middle of December, Campbell had made a number of timed attempts, but the highest speed achieved was 264 mph, and therefore still shy of the existing record. Eventually, further modifications to K7's fuel system (involving the fitting of a booster pump) fixed the fuel-starvation problem. It was now the end of December and Campbell was all set to proceed, pending only the arrival of suitable weather conditions.

On 4 January 1967, Campbell mounted his record attempt. He was killed when K7 flipped over and broke up at a speed in excess of 300 mph (480 km/h). Bluebird had completed a perfect north-south run at an average of 297.6 mph (478.9 km/h), and Campbell used a new water brake to slow K7 from her peak speed of 315 mph (507 km/h). Instead of refuelling and waiting for the wash of this run to subside, as had been pre-arranged, Campbell decided to make the return run immediately.

Not the K7, this is the K777, a full size jet powered water speed record boat that could be run at Coniston and other venues - and who knows, given the right conditions, may even set a new WSR. If that was on the cards, we'd suggest a horizontal tailfin and wind and water tunnel testing.

The second run was even faster; as K7 passed the start of the measured kilometre, she was traveling at over 320 mph (510 km/h). However her stability had begun to break down as she traveled at speed she had never achieved before, and the front of the boat started to bounce out of the water on the starboard side. 150 yards from the end of the measured mile, K7 lifted from the surface and after about 1.5 seconds, gradually lifted from the water at an ever increasing angle, before she took off at a 90-degree to the water surface. She somersaulted and plunged back into the lake, nose first.

The boat then cartwheeled across the water before coming to rest. The impact broke K7 forward of the air intakes (where Donald was sitting) and the main hull sank shortly afterwards. Campbell had been killed instantly. Mr Whoppit, Campbell's teddy bear mascot, was found among the floating debris and the pilot's helmet was recovered. Royal Navy divers made efforts to find and recover the body but, although the wreck of K7 was found, they called off the search, after two weeks, without locating his body.

The cause of the crash has been variously attributed to Campbell not waiting to refuel after doing a first run of 297.6 mph (478.9 km/h) and hence the boat being lighter; the wash caused by his first run and made much worse by the use of the water brake, (These factors have since been found to be not particularly important. The water brake was used well to the south of the measured distance, and only from approx. 200 mph (320 km/h) The area in the centre of the course, where Bluebird was traveling at peak speed on her return run was flat calm, and not disturbed by the wash from the first run, which had not had time to be reflected back on the course.

The fuel tank was in approximately the same position as K7's centre of gravity, and therefore had little impact on the boats weight distribution), and potentially a cut-out of the jet engine caused by fuel starvation. (The configuration of K7 at high speed meant that the thrust of the jet engine provided a downward pressure at the bows of the boat. K7 was operating at her absolute limit in terms of a nose up pitching angle of 6'. A sudden loss of power caused by an interruption to fuel flow would mean that this down-thrust was lost and K7's bows would have risen above the 6' safe limit) Some evidence for this last possibility may be seen in film recordings of the crash below - as the nose of the boat climbs and the jet exhaust points at the water surface no disturbance or spray can be seen at all.

Controversy over the recovery

Restoration and future running

The gravestone of Donald Campbell CBE. RIP

LINKS & REFERENCE

Daily Mail Bluebird speedboat rebuilt wreckage http://www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?t=1959632

In the unlimited powerboat racing category jet powered hydroplanes routinely exceed 200mph. These boats also corner rather well, to be able to race a course. DC would have approved.

K7

Models

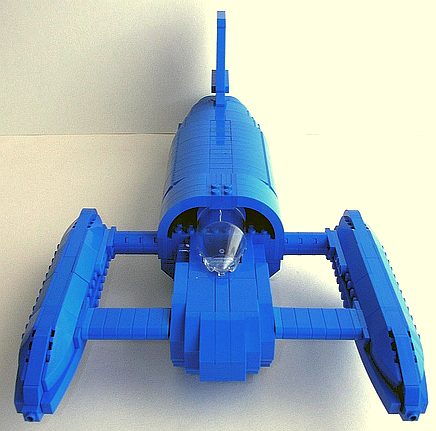

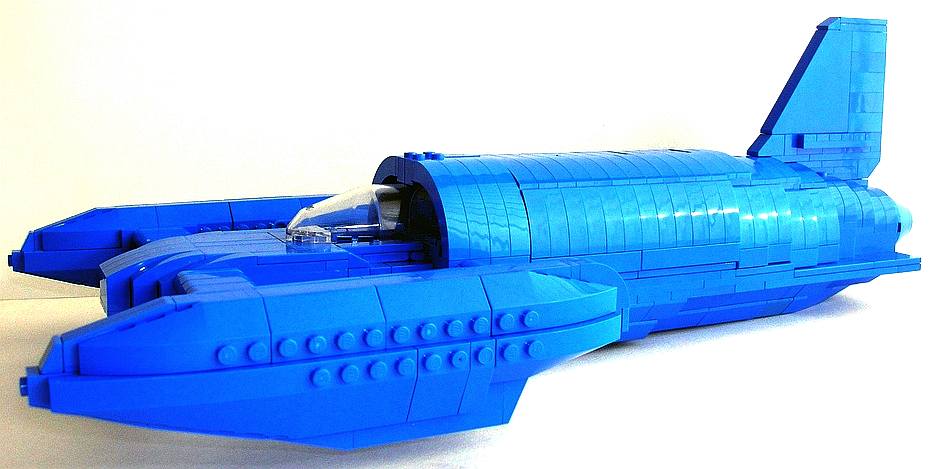

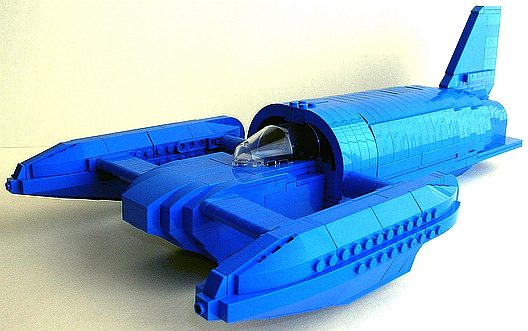

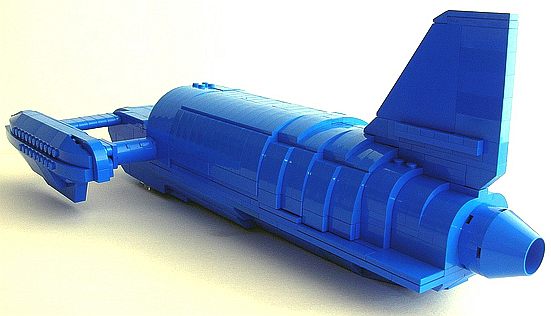

A superb Lego tribute to Donald Campbell and the K7

Not a model of the K7 at all. This is a robotic boat that is powered by electricity and is designed to vacuum up plastic from our polluted oceans. The boat looks remarkably like the jet powered craft piloted by Donald Campbell - as it is seen here without wings. With solar wing panels, other energy harvesting apparatus and a UAV landing pad, the boat looks completely different.

SIR MALCOLM CAMPBELL'S BLUE BIRDS

A 1/12th scale model 660mm long by Touchwood

DONALD CAMPBELL'S BLUEBIRDS

The blue bird legend continues; the first road car to use our blue bird trademark is an electrically powered long distance runner that uses cartridges to recharge instantly (in under a minute). This is achieved with built in power loaders, enabling the car to recharge at any road stop where a cartridge is waiting to be picked up. The first event where this may be tested is the UK Cannonball ZEV Run, a road trip of close on 900 miles from Lands End to John o'Groats.

|

||

|

This

website is Copyright © 2017 Bluebird Marine Systems Limited.

The names Bluebird™, Blueplanet BE3,

Ecostar DC50™

and the blue bird in flight

|

||