|

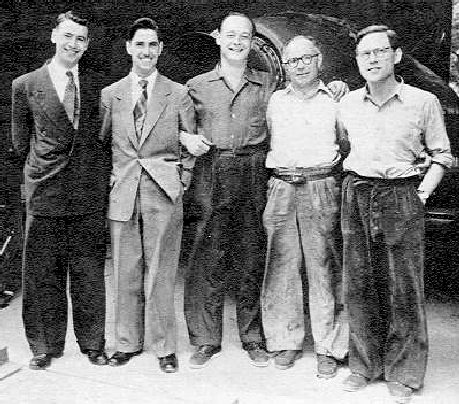

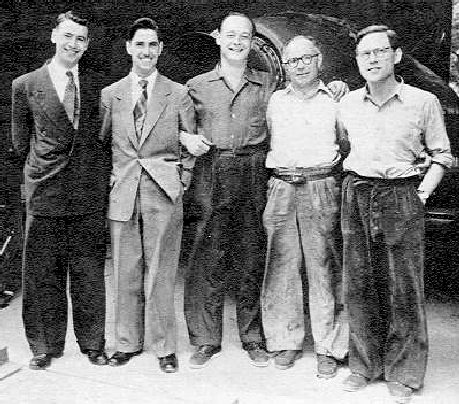

Ken

Norris (centre) designed the

Bluebird K7 for Donald Campbell. After Reid

Railton retired from designing land and water speed craft following

the death of John Cobb. There was a

void, which Ken and his brother Lewis Norris filled most admirably along

with practical guidance from Leo Villa (left).

WHITE

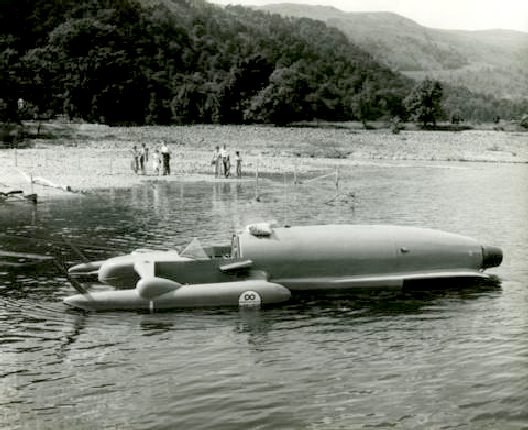

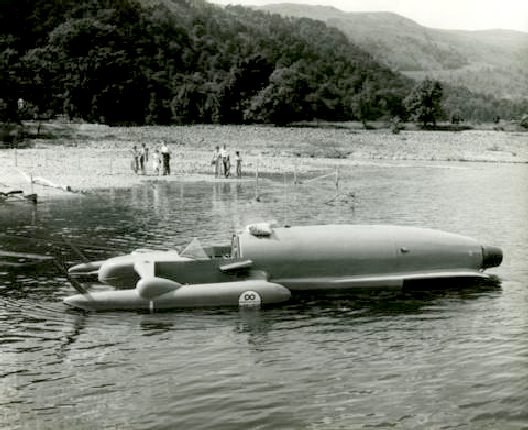

HAWK WORLD WATER SPEED RECORD BOAT K5 1951

The

White Hawk or K4

was the first water speed record project to enlist the help of Ken Norris.

The K4 was a 25ft jet-powered hydrofoil,

the brainchild of ex-submarine lieutenant (RN) Frank Hanning-Lee. Frank

was related to Horatio

Nelson a fact which may have decided Ken on pitching in, or more than

likely it was the lure of the 1943 Whittle turbojet engine, since Ken was

a keen aviation student. So it was that the Hanning-Lees invited Ken

Norris 'to do their sums for them' and before long Norris found

himself doing the entire design work himself, until he realised that he

would not be paid

for his labours. So it was that Ken Norris pulled out of the project.

Of

this project Ken Norris is quoted as

saying:

'I

concluded that above a speed of 70 mph, the hydrofoil would be subject to

cavitation. Unlike a hydroplane, which generates lift by being on top and

skating over the surface, the hydrofoil is immersed fully, generating lift

on both the top and the bottom surface. As the speed increases, so the

pressures round the foil change until eventually the pressure on the top

surface can become so low that the aerated water tends to create a

complete bubble and break down the lift on the top surface. At that point

one might lose as much as two-thirds of the lift and at that speed the

vessel will drop back into the water. So it rides up for a start, gets up

to surface speed and then drops down, rather like a stall with an

aeroplane. I believe that this is what happened to the White Hawk,

although this doesn't mean that their achievement wasn't pretty good.'

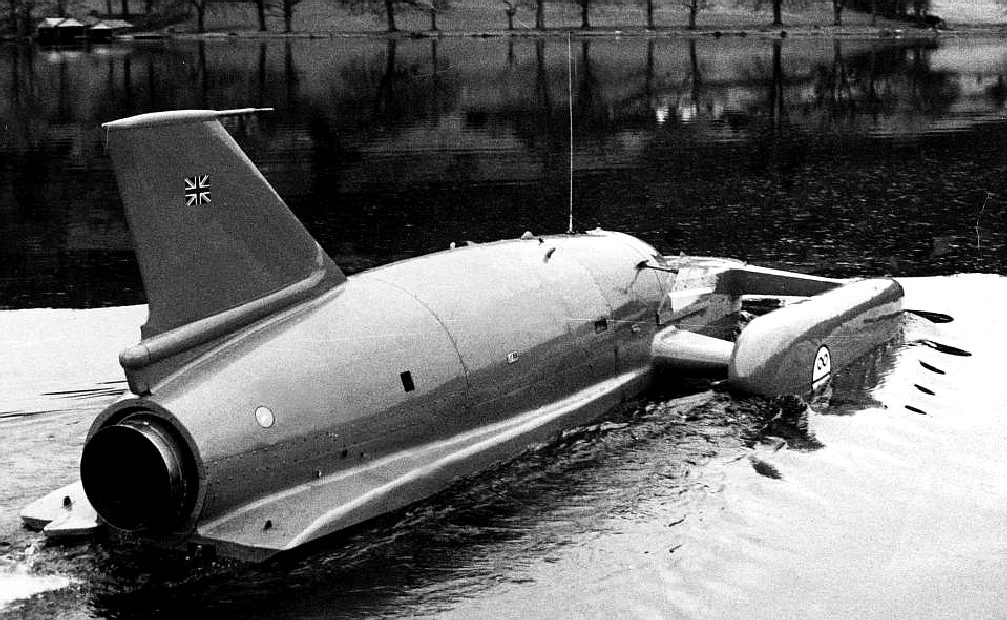

The

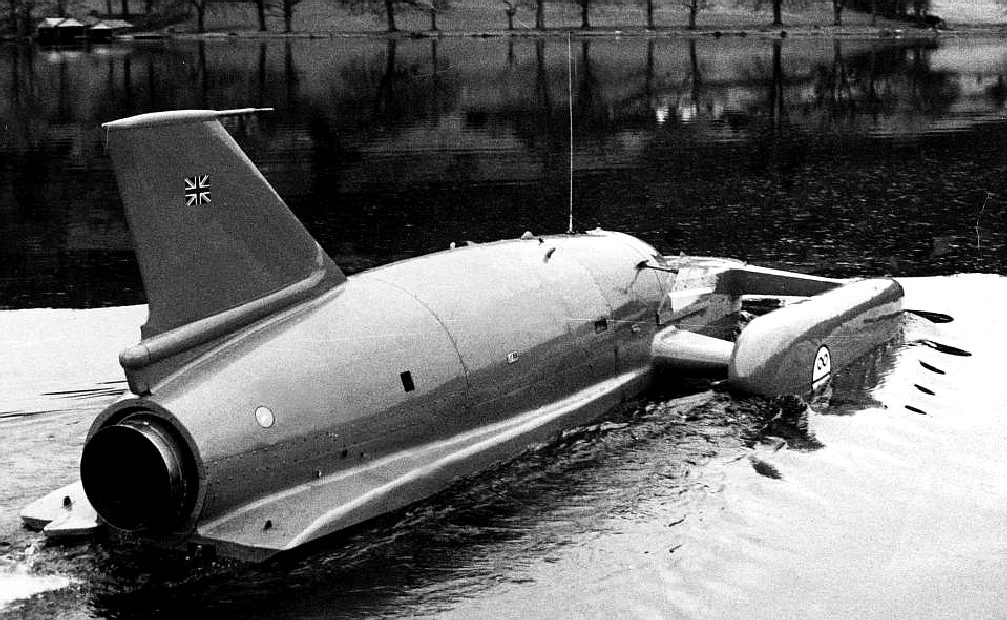

K7 at Ulswater in 1955

BLUEBIRD K7

With Donald Campbell, Ken was employed on a firm financial footing and so

earned the loyalty of his engineers. DC set seven world water speed records in K7 between 1955 and

1964 of which Ken and Lewis would have been proud.

The first of these occurred at Ullswater on 23 July 1955, where he set a record of 202.15 mph (324 km/h). Campbell achieved a steady series of subsequent speed-record increases with the boat during the rest of the decade, beginning with a mark of 216 mph (348 km/h) in 1955 on Lake Mead. Subsequently, four new marks were registered on Coniston Water, where Campbell and Bluebird became an annual fixture in the later half of the fifties, enjoying significant sponsorship from the Mobil oil company and then subsequently BP. There was also an unsuccessful attempt in 1957 at Canandaigua in New York state in the summer of 1957, which failed due to lack of suitable water conditions. Bluebird K7 became a popular attraction, and well as her annual Coniston appearances, K7 was displayed extensively in the

UK, USA, Canada and Europe, and then subsequently in

Australia during Campbell's prolonged attempt on the land speed record (LSR) in 1963 - 64.

In order to extract more speed, and endow the boat with greater stability, in both pitch and yaw, K7 was subtly modified in the second half of the 1950s with the installation of smoother streamlining, a blown cockpit canopy and, from 1958 onwards, a small wedge shaped tail fin, modified sponson fairings, that reduced aerodynamic lift, and a fixed

hydrodynamic fin, fixed to the transom to aid hydrodynamic stability, and exert a marginal downforce on the nose. Thus she reached 225 mph (362 km/h) in 1956, where an unprecedented peak speed of 286.78 mph (461.53 km/h) was achieved on one run, 239 mph (385 km/h) in 1957, 248 mph (399 km/h) in 1958 and 260 mph (420 km/h) in 1959.

Campbell then turned to the LSR, and after surviving a high speed crash in his Bluebird

CN7 turbine powered car, and once

again relied on Ken Norris who confided in our IP consultant that he prepared

hundreds of drawing the old fashioned way on paper.

DC

spent a frustrating two years in the

Australian desert, battling adverse conditions. Finally, after Campbell exceeded the LSR on Lake Eyre in 1964, at 403.10 mph (648.73 km/h) in Bluebird CN7, Campbell snared his seventh water speed record on 31 December 1964 at

Dumbleyung Lake, Western Australia, when he reached 276.33 mph (444.71 km/h), with two runs at 283.3 mph (455.9 km/h) and 269.3 mph (433.4 km/h) completed with only hours to spare on

New Year's Eve 1964.

This made Campbell and K7 the world's most prolific breakers of the Water

Speed Record and all thanks to the designs of Ken and Lewis Norris. Campbell became the only person to break both the

Land Speed Record and the Water Speed Record in the same year.

The

CMN-8 mock-up with admirers

CMN-8

BLUEBIRD MACH 1.1 ROCKET CAR

The

Bluebird Mach 1.1 (CMN-8) was a design for a rocket-powered supersonic land speed record car, planned by Donald Campbell but thwarted by his subsequent death

in K7 in 1967.

Donald Campbell decided a massive jump in speed was called for following his successful 1964 LSR attempt in Bluebird CN7. His vision was of a supersonic rocket car with a potential maximum speed of 840 mph, referred to as Bluebird Mach 1.1. Norris Brothers were requested to undertake a design study.

Campbell, ever superstitious, chose a lucky date to hold a press conference at the Charing Cross Hotel on 7 July 1965 to announce his future record breaking plans:

“ ... In terms of speed on the earth’s surface, my next logical step must be to construct a Bluebird car that can reach Mach 1.1. The Americans are already making plans for such a vehicle and it would be tragic for the world image of British technology if we did not compete in this great contest and win. The nation whose technologies are first to seize the “faster than sound” record on land will be the nation whose industry will be seen to leapfrog into the 70s or 80s. We can have the car on the track within three years" ”

Bluebird Mach 1.1 was to be rocket-powered. Ken Norris had calculated using rocket motors would result in a vehicle with very low frontal area, greater density, and lighter weight than if he went down the jet engine route. Bluebird Mach 1.1 would also be a relatively compact and simple design. Norris specified two off-the-shelf Bristol Siddeley BS.605 rocket engines. The 605 had been developed as a take-off assist rocket engine for military aircraft and was fuelled with kerosene, using hydrogen peroxide as the oxidizer. Each engine was rated at 8,000 lbf (36 kN) thrust. In Bluebird Mach 1.1 application, the combined 16,000 lbf (71 kN) thrust thrust would be equivalent of 36,000 bhp (27,000 kW; 36,000 PS) at 840 mph (1,350 km/h).

The compact size of the rocket motors enabled Norris to design a vehicle with a very low cross-sectional area. A dart-like configuration was chosen, with two closely paired front wheels behind the nose-mounted cockpit and two rear wheels 8 ft (240 cm) apart, faired into stabilising fins. The design was expected to be inherently stable in a straight line. The main structure of the car was both elegant and simple, yet it would ensure significant torsional strength and also allow separate storage of the two liquids used as the propellant. The main chassis would be a flat box-like structure with internal rib strengthening, not unlike the chassis of Bluebird CN7. This would provide the frame to which were attached the rocket engines, one above and one below, as well as the propellant tanks – hydrogen peroxide on top, kerosene underneath. The frame would also house the torsion bar rear suspension. Clad in a slim pencil-shaped body with rear outrigger fins, the vehicle would feature a recumbent driving position. The wheels were to be machined from solid aluminium billets. As they were not required for propulsion, but merely to support the car, there would be no need for tyres.

Various dimensions were considered and eventually a full-scale mock-up of the car was built measuring 27 ft 8 in (843 cm) long, 8 ft 6 in (259 cm) wide at the rear wheels, with an overall height of just 3 ft 7 in (109 cm). Ground clearance was projected to be only 4.5 in (11 cm), giving Bluebird Mach 1.1 a very low centre of gravity and roll centre. The predicted weight was 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) including propellants. Bluebird Mach 1.1 would thus have a power-to-weight ratio of 22,000 bhp (16,000 kW; 22,000 PS) per tonne.

Interest in the project was such that the Jamaican Government offered to construct a 14-mile (23 km) track to host the record.

After Campbell's death, the project continued at a low key for some years, still involving Leo Villa, with Norris as Design Consultant from 1968-1971. In 1973,

Nigel McKnight became involved, but failed to raise the necessary sponsorship.

Ken Norris also helped Nigel MacKnight with his Quicksilver

WSR project.

The model disappeared and its present whereabouts are unknown. It was possibly buried in building foundations, along with the wrecked sponsons

of Bluebird K7. Time

will tell.

The project is little-known today, although some model makers offer replicas.

The full story of Campbell's stillborn rocket car is told in 'Donald Campbell Bluebird and The Final Record Attempt' published in late 2011.

The

K7 at Coniston really moving

The Final Water Speed Record attempt and Donald Campbell's death

In June 1966, Campbell decided to once more try for a water speed record with K7: his target, 300 mph (480 km/h).

Ken knew the K7 was reaching the limit of its useful life, but the team

were bound by the rules at the time which allowed no aerodynamic devices

to control lift. The tailfin did not control lift and it could be argued

that a fin the simply acted like the feathers on an arrow, also provided

no lift - but it was not to be.

K7 was fitted with a lighter and more powerful Bristol Siddeley Orpheus engine, taken from a Folland Gnat jet aircraft, and lent to the project by the MOD, which developed 4,500 pound-force (20 kN) of thrust. The new K7 had a vertical stabiliser (also from a Gnat Campbell had purchased ) and a new hydraulic water brake designed to slow the boat down on the five-mile

Coniston course.The boat returned to Coniston for trials in November 1966. These did not go well; the weather was appalling and K7 destroyed her engine when the air intakes collapsed under the demands of the more powerful engine, and debris was drawn into the compressor blades. The engine was replaced, Campbell using the unit from the scrapped, crash-damaged Gnat aircraft that he had purchased at the project's

start. The original engine remained outside the team's lakeside workshop for the rest of the project, shrouded in a tarpaulin.

By the end of November, after further modifications to alter K7's weight distribution, some high-speed runs were made, but these were timed at well below the existing record. Problems with the fuel system meant that the engine could not develop maximum power. By the middle of December, Campbell had made a number of timed attempts, but the highest speed achieved was 264 mph, and therefore still shy of the existing record. Eventually, further modifications to K7's fuel system (involving the fitting of a booster pump) fixed the fuel-starvation problem. It was now the end of December and Campbell was all set to proceed, pending only the arrival of suitable weather

conditions .........

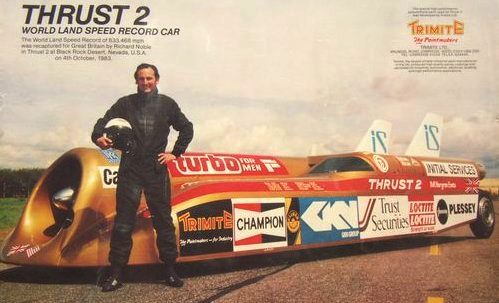

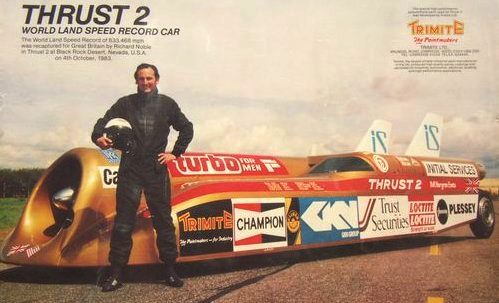

Anyone

who has met him will tell you Richard is a British Bulldog, er, Bloodhoud

THRUST

2

Ken

was also involved in Richard Noble's Trust projects. He vetted and so

introduced John Ackroyd to Richard. John

worked in a similar fashion to Ken, using a drawing board and slide ruler

for their workings. GHOSTS

FROM THE PAST Donald Campbell's speedboat Bluebird was today embarking on a new journey a day after being raised from the depths of Coniston Water.

Under a veil of secrecy, the wreckage of the jet-powered craft was being transported 100 miles by road on board a trailer - a little slower than its previous top speed of 300mph - to a workshop in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Any slim hopes of finding Campbell's body inside Bluebird disappeared yesterday after police officers confirmed that no remains were found when the boat was brought ashore.

But the confirmation means work can begin straightaway on restoring the craft to its former glory.

Bill Smith, the engineer who led the diving expedition team which raised Bluebird from the lake-bed 34 years after Campbell's fatal crash, said it would take two or three days to painstakingly clean the mud and silt from the outside of the boat.

It would then be dried and waxed before being wrapped in protective polythene and kept under lock and key until the adventurer's family made a decision about its future.

The rear of Bluebird has stayed remarkably intact despite lying on a bed of silt and weeds 150ft below the lake's surface but the cockpit completely disintegrated in the crash, leaving a mangled mass of aluminium to the front.

The man who designed Bluebird, Ken Norris, now in his 70s, said he would examine the craft to try to complete the jigsaw of how the accident happened.

Mr Norris said yesterday: "At the time I never realised how Donald came to crash. It is only over the last few weeks that I have gone through it all again.

"I have to put it down to a combination of things, the rough conditions, the speed he was going, but ultimately because Bluebird started rolling.

"There are things we know now that Donald would not have known. Maybe if he had used the brake before coming off the throttle, it would have been different."

Yesterday's operation, which began at 5am and culminated in Bluebird being towed ashore at midday, brought to an end Mr Smith's four-year quest to raise her from the depths of Coniston Water.

The adventurer's widow, Tonia Bern-Campbell, and close friends saw for the first time the horrific damage to the front of the jet-powered craft as divers slowly lifted it from the lake.

It is thought Mrs Campbell, his daughter Gina and the diving team want Bluebird to be eventually returned to Coniston where it can be viewed in a museum.

Mrs Bern-Campbell, 64, who had travelled from her home in California to watch the salvage operation, was said to be "understandably upset" as her late husband's craft loomed out of the murky waters.

She watched from a jetty as Bluebird's tail-fin, complete with distinctive Union Jack and a streak of blue shining through a thick layer of mud and silt, poked through the surface of the lake.

Forty-five-year-old Campbell was attempting to break his own world water speed record of 276mph when he went out on Coniston Water on January 4, 1967.

He reached a speed of 297mph on the way out but on the return leg, as the craft reached an estimated 300mph, Bluebird's nose lifted from the surface and somersaulted before crashing, killing him instantly.

A

CN7 board meeting - Leo, Ken, Lew and Donald

2009 FEB 13 LEWIS NORRIS

Lew Norris, who has died aged 84, helped to design the high-speed Bluebird boats and car in which Donald Campbell broke post-war water and land speed records; in the 1950s his company, one of the most diverse and innovative of its kind, also invented the automatic seat belt and produced an early go-kart.

Warm, fun-loving and unassuming, Norris first came to attention in 1953 when Campbell decided to press ahead with his Bluebird project despite the death of John Cobb, whose revolutionary

jet-powered Crusader had crashed on Loch Ness in September 1952 during his attempt to exceed 200mph. With Norris and his elder brother Ken, Campbell set out to break the water speed record in the jet-powered Bluebird K7 hydroplane, with the Norrises applying to its design and construction the lessons learned from Cobb's Crusader.

Lew Norris had worked on Campbell's earlier Bluebird K4 boat, designing the new propeller shaft; but while his brother Ken had enrolled at Imperial College to study Aeronautical Engineering, Lew had started as a workshop manager with another brother, Eric, the accountant at Kine Engineering of Horley, where Donald Campbell was part-owner.

On New Year's Eve 1952, shortly after Lew and Ken had set up their own engineering design consultancy – Norris Brothers, at Haywards Heath – Campbell approached them at a party at his house. "We had a bit of a romp, had the music on, laughed around a bit," Ken Norris remembered. "Then Donald said to Lew and me, 'Now that you're together, how about designing me a boat?'"

After conducting a grisly analysis of the forces that had killed Cobb, the Norrises created an all-metal hydroplane which became Bluebird K7, with Lew the co-chief designer.

Neither Lew Norris nor his brother was present when disaster struck, but as they flew up to the Lake District later that day they asked themselves if there had been any design flaw in Bluebird that could have been responsible. The answer was emphatically not. Before his death, in gratitude for his work on K7, Campbell had given Norris a brand new

Austin saloon to replace his old pink Ford Consul.

In December 1964, Bluebird K7, with Campbell at the wheel, had set a new world water speed record of 276.33mph at Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia. Five months earlier, on Lake Eyre (South Australia), Campbell had set a new official land speed record of 403.1mph in Bluebird CN7, the car Norris had designed to aircraft standards, with the safety of its driver paramount. Campbell had sustained only minor injuries when, in September 1960 on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, CN7 crashed at more than 300mph, flying through the air for 300 yards and bouncing three times.

The

CN7 with it's master at Lake Eyre - It doesn't get much better than

this.

CONSULTANT

- Ken

Norris was consulted at the very early design stages of the BE3. His

advice was to use a strong steel frame and 4 wheel drive. Much of this was

practical advice to do with working in a salty environment and having to

make repairs - nigh on impossible with the CN7's honeycomb aluminium

monocoque construction. Advice well heeded. The classic lines of this racing

car were inspired by Reid

Railton and his designs for the Napier Lion and Rolls

Royce engined Blue Bird LSR cars in the 1930s, the Blueplanet BE3

features instant battery recharging using the patent

Bluebird™ cartridge exchange system under license from BMS.

This LSR is also solar assisted. She is designed for speeds in excess of

350mph using clean electricity. Imagine the spectacle of this beautiful

vehicle speeding across the salt at Bonneville,

or flying past on the sand at the Daytona

or Pendine

beaches. To hire this vehicle for your venue please contact BMS

and ask for Leslie or Terry. The BE3 team need at least 3 months advance

notice of events. The blue bird

legend continues. You can see the frame of the BE3 on display at Campbell

Hall in Sussex.

The "honeycomb sandwich" used in its construction is still the basis of the crash protection shell used in Formula 1 cars today, albeit with new, stronger and lighter materials. Although CN7 broke the record, it never reached its maximum potential speed because of Campbell's untimely death on water; but evidence from its record runs shows that it was almost certainly capable of around 550mph on the right surface, well above the present wheel-driven record. Fifty years after their design, the Bluebirds remain the only vehicles to break both world records in the same year.

Lewis Hunt Norris was born on September 20 1924, the youngest of six sons and two daughters of the engineer in charge of the gasworks at Burgess Hill, Sussex. Four of the brothers became qualified engineers in different disciplines, one an accountant, and one was killed in the

Battle of Britain.

After Lewes Grammar School and West Ham Technical College, Lew Norris served his apprenticeship with

Harland and Wolff at its London docklands shipyard, building landing craft for D-Day. After the war he went to Burma to work for Burmah

Oil, and had a narrow escape during the Communist takeover of the country while waiting on a jetty for a boat to start his journey home. He heard some gunfire and the sound of a fast boat, so he lay flat on the jetty and, because the water level was 15ft below, he remained undetected.

Norris became involved with Donald Campbell when he did some design work for Campbell's company, Kine Engineering. Whilst there he was responsible for modifications to the old K4 propeller-driven hull piloted by Campbell's father,

Sir Malcolm Campbell, including the fitting of a

jet

engine; but the hull design was not suitable, and the project was scrapped.

In 1952 Lew Norris, along with Eric and Ken, set up an engineering design consultancy, Norris Brothers. When Donald Campbell decided to attempt the water speed record in a new jet-powered Bluebird K7, Lew and Ken Norris were the obvious choice as designers. A few years later, when Campbell decided to attack the land speed record, the Norrises and their design draughtsman Donald Stevens drew up the specification, with Lew in charge of all mechanical aspects, including modifying the Proteus jet engine.

Apart from the Bluebirds, Norris Brothers was responsible for many original concepts, which most famously included the automatic seat belt fitted to all cars today. Early seat belts were either fixed length or were activated by forward movement only.

The Norris design worked on a pendulum principle that activated the lock if the vehicle moved rapidly in any direction. Because the Norris company was badly

under-funded it accepted an offer of one British manufacturer to produce detailed drawings and prototypes. This firm then started production under its own name and refused to pay royalties. The subsequent court case found in the manufacturer's favour because its drawings predated the Norris

patent application.

Through Norris Brothers' involvement with Bluebird, in 1960 British Petroleum asked Lew Norris to design a low-cost "fun" racing vehicle which would be safe for young people. Using a lawnmower engine and simple tubular chassis, he developed an early go-kart. Norris had the experience of testing it at 60mph with his bottom skimming only two inches above an old

RAF runway.

Other noteworthy firsts were air-supported buildings; a rotary engine for Vincent motorcycles; a high-gap micro-switch which became an industry standard under the Pye name; a concrete pump; and underground coal gasification plants.

As the company grew, Lew Norris realised that design alone would never make much money; so while Ken concentrated on the design aspects of the business, Lew developed the manufacturing side.

The first product was a ball valve made under a joint-venture agreement with the Worcester Valve Company of Massachusetts. This was eventually bought out by a major British conglomerate, but not before Norris and his team had developed a control system for it which he licensed back to Worcester in America – he became Worcester's vice-president.

Despite Worcester Valve UK being vastly smaller than its competitors it became, and remains, a market leader. Initially this was through Norris introducing advanced management and

computer systems long before they became fashionable. Subsequently he developed and patented the Flotronic pump, renowned for its ease of maintenance in the process industries. Norris also developed other companies that designed and produced spool valves, packaging machinery, lift trucks and explosion-proof boxes.

Success brought a good income, and Norris moved to Alderney in the Channel Islands, from where he piloted his twin-engined aircraft across to Shoreham until he was nearly 75. He then went to live at

Hove, Sussex, and remained active in his companies until prevented by ill-health.

Despite their major contribution to British engineering, the Norris brothers were never honoured by their country. Ken Norris died in 2005.

Lew Norris is survived by his wife Beryl and their three daughters.

The

K7 team: Lewis and Ken Norris, Donald Campbell, Leo Villa and Tom-Fink

THE

TELEGRAPH 15 APRIL 2001

THE 34-year-old mystery of what caused the jet-powered boat Bluebird to crash, killing its driver Donald Campbell, has been finally solved following the recovery of the craft from the bottom of

Coniston

Water, Cumbria.

Ken Norris, who was the co-designer of Bluebird, has examined the wreck and concluded that the disaster, which happened as Campbell attempted to set a 300mph water speed record, was caused by a combination of an inherent design flaw in the boat and by Campbell throttling back in an attempt to slow down.

After the accident, on January 4, 1967, many theories about the cause of the crash were advanced but, without the remains of the boat, it was impossible to make a conclusive judgment. Among the suggested causes were Bluebird hitting a log or aquatic birds.

In the wake of the salvage operation, Mr Norris analyses the crash in his book The Bluebird Years - Donald Campbell and the Pursuit of Speed, for which he reproduced the circumstances of the last fateful run. At 79, he still constructs jet-powered boats and is the chief designer of the latest contender for the British water speed record, Quicksilver. According to Mr Norris, the dynamics of Bluebird allowed its nose to pitch, or rise up, only six degrees from the surface of the water before it risked becoming airborne and crashing.

What neither he nor anyone else involved in the 1967 attempt realised was that the craft's triangular design meant that choppy conditions caused it to tramp, or roll from side to side, in a skewed motion. This unusual movement caused the nose to rise above five degrees.

One safeguard against Bluebird's nose lifting dangerously high was the thrust from the jet engine, which helped counter the lift. However, Campbell had reduced the thrust seconds before the crash, thereby allowing the craft's nose to rise further. As film of the event shows, Campbell, who was attempting to break his own 276mph water speed record, drove the 12-year-old craft once across the lake, then turned around and made a return run.

He reached an unofficial speed of 330mph before throttling back the engine to slow down. As speed decreased Bluebird suddenly lifted up, nose first, rose into the air and somersaulted, before sinking. Mr Norris said: "On the first run it was beautiful, absolutely steady. On the return run we had to contend with the wash from the boat itself, the slight swell and the wake from the water brake which he had used to slow down on the first run."

He said: "We all knew that when Bluebird reached six degrees of pitch it would take off. But you lose one degree through speed, you also lose about one and a half degrees from the swell. The rest was lost from the tramping action. "

He said: "According to my sums the nose went up to 5.2 degrees. When he throttled back it reduced thrust which caused the nose to rise by another 0.8 degrees, taking it up to six degrees. The irony is that by slowing down he actually caused the accident."

The wreck was salvaged last month following a four-year search by a team of divers led by Bill Smith, an underwater surveyor. During the operation the team believed that they had located Campbell's missing body on the lake bed, but a closer examination proved it to be a false alarm.

Although the foot and mouth epidemic has temporarily halted the search for his body they are still hopeful that it will be found when diving is resumed. Examination of the wreck revealed that its fuel tank was almost empty at the time of the accident. Mr Norris confirmed that fuel problems could also have resulted in a fatal drop in thrust of the craft's engines.

It was also apparent that Campbell had tried to use the boat's water brake, a hydraulic ram that extends six inches below the craft when activated, to try to save himself. Mr Norris said: "It drastically reduces speed. He had obviously used it, but too late."

Mr Norris believes that by the time the water brake was fully activated Bluebird had already become airborne, rendering it ineffective. He said: "If the boat was still on the surface of the water when he used it, it could have saved him."

SIR

MALCOLM CAMPBELL'S BLUE BIRDS

Sunbeam

Napier

Lion

Rolls

Royce

K3

K4

DONALD

CAMPBELL'S BLUEBIRDS

K7

CN7

CNM8

LINKS

https://www.facebook.com/bluebirdk7 https://www.facebook.com/bluebirdk7 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird_Mach_1.1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird-Proteus_CN7 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird_Mach_1.1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird-Proteus_CN7 Bluebird

Project http://www.bluebirdproject.com

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird_Mach_1.1

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/4735806/Lew-Norris.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-29162/Bluebird-embarks-new-journey.html

http://www.johnshintonmodels.co.uk/showcase2.htm

http://www.johnshintonmodels.co.uk/showcase2.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird_Mach_1.1

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/4735806/Lew-Norris.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-29162/Bluebird-embarks-new-journey.html

The

headstone of a great sportsman, RIP

|