|

Photograph

It

is a fact that most accidents at sea are caused through human error. We are

talking about thousands of marine

incidents every year, some with serious and with tragic consequences

such as the Costa

Concordia grounding and of course the Titanic

sinking. Imagine then the possibilities for safer marine

transit if robotics could be employed to reduce these statistics.

The

problem is that with current thinking nobody looked far enough into the

future to see that with automation many accidents could be avoided. This

is the case with ships at time of writing and it was and most likely is

still the case with drones, where the authorities are playing catch up.

Why are they playing catch up?

The

simple answer to that is that technology is advancing faster than any

government or other body can re-write the rule books. The automobile is

one case precedent, where a man had to run in front of a car with a red

flag to warn pedestrians of the potential danger.

There

is of course nothing to stop anyone putting an autonomous ship to sea in

international waters, where the only ramifications would be a prosecution

in the event of an accident. That would lead to a court being presented

with information as to any accident - when we believe that the black

box would be more than likely to prove that the other vessel under the

command of a human

was at fault. Such a case is inevitable eventually. We need only to look

at the Google car to see how reliable autonomous cars are. The only

accident involving these wagons was caused by a human driver.

Unmanned

vessels have been roaming the high seas for decades surveying underwater

and sampling the seawater to allow us to build up a better picture of the

changing ocean makeup due to climate

change. As far as we know there are no reports of an unmanned craft

causing an accident.

SEAVAX

This

is important where autonomous workboats like SeaVax

are concerned. The law is clear that provided a lookout is monitoring the

sea in the immediate vicinity of the vessel, that in that case international

conventions for safety at sea are satisfied. It matters not how this is

achieved or that any electronic eye (lookout) has sharper vision and

reflexes than any human as a result of the electronic enhancement, with additional safety features - such that the

abilities of the human lookout are superior. For, nobody can be accused of

sloth if they are faster and more accurate than any biological counterpart

acting without electronic aids.

Or is that the argument that will require another "red

flag" situation

before the rule makers bow to common sense.

Where

GPS is denied for any period of time, the vessel may calculate its

position in time honoured fashion using dead reckoning techniques, a

method of navigation that is used for the Mars Rover where there is of

course, no GPS.

On

this page we take a look at the media reports relating to autonomous

vessels.

Have

you

MARITIME

JOURNAL 25 AUGUST 2017

According to Charles Hattersley, Partner and Head of Marine at Ashfords, a Law practice in Exeter, UK, unmanned workboats are quickly appearing over the

horizon, but the legal framework may end up playing catch-up with the rapid technological progress.

The International Maritime Organisation will shortly consider changing the international Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) to allow ships with no captain or crew to become operational.

The offshore industry, with the assistance of the IMO, is developing technology for ships that will operate autonomously in open water and be remotely controlled by a land based ‘captain’ when entering or leaving port.

Although the processes of changing the rules with SOLAS and the IMO are slow, progress is being made and by no later than 2024 some workboats operating off European coasts will almost certainly be unmanned.

LEGAL ISSUES

The important question for the legal and insurance professions is how will the operation of unmanned craft be regulated? Will the operation of these vessels require the creation of an entirely new legal framework?

The current regulatory framework is codified in large part by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 – (UNCLOS). This refers expressly to ‘ships’ which raises the fundamental question of whether unmanned craft are in fact ‘ships’. Under English law a ship is defined as including ‘every description of vessel used in navigation’. The term ‘navigation’ is undefined. There are a few cases that offer guidance but none are definitive. The best view is that, under English law, there is nothing in the authorities that would categorically preclude an unmanned craft from constituting a ship. This means that unmanned ‘ships’- which will include workboats - should comply with the current maritime regulatory framework and have the benefit of the standards and certification regime under

SOLAS. Owners would, as a result, be able to limit their liability under the Limitation of Liability of Maritime Claims Convention 1976 (as amended). However, in order to do so they must comply with regulatory requirements.

Flag state obligations are set out in UNCLOS article 94 which states flag states must execute effective jurisdiction over their flag ships and ensure that they are adequately crewed with suitable personnel provided. Whether remote controllers can constitute unknown ship masters is an undecided point. ‘Master’ is not defined under UNCLOS although several domestic laws define the term as simply the individual having ‘command’ or ‘charge’ of a ship.

Under Regulation 14 of SOLAS contracting governments undertake that each of its ships shall be both ‘sufficiently and efficiently manned’ and that ships' manning requirements are established by a transparent documentary procedure. There is no express requirement for ships to have at least one seafarer on board - nevertheless regulation 14 still presents a conundrum for the unmanned vessel because, although there is a requirement for manning adequacy, there is not an outright prohibition of unmanned ships. The issue to be addressed by IMO and SOLAS is whether or not safety will, in any way, be compromised.

SIGNALLING AND COLLISION AVOIDANCE

The most important provisions are, of course, the International Regulations for Prosecuting Collisions at Sea 1972 (COLREGS).

A relevant COLREG provision is rule 2. The rule confirms the primacy of adherence to good seamanship over a doctrinaire compliance with the letter of the Rules and that in select circumstances alternative action may be required. In this respect ‘seamanship’ involves the adequacy of the ship's crew.

Arguably the most pressing issue is that posed by rule 5, ie., the extent to which an unmanned ship can maintain a ‘look out by sight and hearing …’. The question is whether a lookout may be lawfully provided by alternative technological means. Unmanned craft can be fitted with cameras and sensors of such sophistication that a very thorough projection of the vessel's vicinity can be streamed to the shore command. The important point therefore is whether this can be said to be a ‘proper lookout’.

This issue has not been decided by the English Courts although authorities have held that both shore based assistance and ‘technical advancements’, in given situations, do comprise essential aspects of the lookout obligations.

However, there is no certainty whether remote control, using the most sophisticated optical and aural sensors, will satisfy the rule 5 obligations. Additionally, unmanned ships will not enjoy any navigational priority over their manned counterparts under COLREGS in circumstances where communications with the unmanned ship are lost - for instance by lack of satellite coverage. It is possible the ship may then claim to be ‘not under command’ ie rule 18 would apply and this would place the onus on other vessels to take necessary action to avoid

collisions.

CONCLUSIONS

The wording of the existing regulatory regime for unmanned workboats is problematic. The real challenges are twofold.

First, is the current absence of, and consequent need to develop, standards and practices in relation to the new procedures which unmanned operations introduce. The development of these practices and their international standardisation will be a long term process but such practices are essential. This in turn will make the technology

insurable and will give maritime authorities the confidence to certify the safety of operational support vessels.

The second is an international consensus. In the absence of even an internationally agreed definition of ‘ship’ there is clear scope for disagreement which may limit the development of this embryonic industry. That is why it is so important to establish an international forum for dialogue. Good progress has been made through the CMI in

Paris; however there is, at present, insufficient international engagement for the potential divisive issues to be clarified.

Once these obstacles are overcome then unmanned ships will begin to realise their staggering potential.

AUSTRALIAN

JOURNAL OF MARITIME & OCEAN AFFAIRS, SEPT 2016 - AUTONOMOUS

MERCHANT VESSELS

ABSTRACT:

Research in the design and development of fully autonomous and unmanned merchant vessels has revealed positive results and expected benefits that support their likely implementation on the high seas in the near future. The benefits mainly derive from the removal of the human element which may reduce associated errors; and provide financial savings on crew salaries and omission of crew accommodation.

However, even though the technical concepts for unmanned vessel operation are well established, studies on human interaction with the systems are not as prevalent. This paper highlights the regulatory, legal, safety, human/technology interface and societal concerns posed to the operation of unmanned vessels. This paper argues that the belief in complete reliability and trustworthiness of fully automated ships is unrealistic, and in doing so, questions its commercial viability.

This paper concludes that the maritime and seafaring industry require further evidence of the validation of the technology before the long-term effects of fully automated vessels can be equated.

By Trudi Hogg & Samrat Ghosh

UK

GOVERNMENT NEWS - CENTRE DEFENCE

ENTERPRISE, AUGUST 15 2016

Polaris Consulting Ltd was funded by the Centre for Defence Enterprise (CDE) to develop a way to support autonomous vessels in global positioning systems (GPS) denied environments.

The company researched and developed an algorithm that combines the outputs from the vessel’s sensors along with prior knowledge of local landmarks and coastal features to provide an estimate of it’s position.

The algorithm consists of 2 phases. Firstly, individual sensors provide position estimates (for example from radar and optical cameras). Then in the second phase, an extended kalman filter was used to combine the positional information from each sensor to derive a final computed position. This took into account how accurate the position provided by each sensor was in different environmental conditions. For example, in foggy conditions, there would be low confidence in the position provided by the camera.

The algorithm was tested using REMBRANDT, a shipping simulator developed by BMT ARGOSS. Within Portsmouth Harbour and the Solent for the chosen route, different environmental conditions were simulated (calm seas, choppy seas, tidal conditions, fog etc) to assess the accuracy of the algorithm. The average deviation in position compared to GPS was less than 35m, a significant achievement, particularly as the maximum deviation was nearly always less than 100m.

Future work will include the addition of new sensors to improve positional accuracy by using navigational markers and buoys as reference points, a mission execution decision module and a test on an autonomous vessel at sea provided by ASV Ltd.

David Bangert, Founder, Polaris Consulting Ltd is quoted as saying:

"Winning funding for 3 CDE proposals has been of huge benefit to Polaris. They have enabled us to apply our analysis expertise to some cutting edge defence problems, build partnerships with other companies, and raise the profile of the business. Like most SMEs, we relish a challenge, and CDE has expanded our horizons and will undoubtedly provide us with new opportunities in the future. It’s also good to be working with like-minded partners to deliver tangible benefits for the UK’s Armed Services."

ABOUT CDE

CDE funds novel, high-risk, high-potential-benefit research. We work with the broadest possible range of science and technology providers, including academia and small companies, to develop cost-effective capabilities for UK armed forces and national security.

CDE is part of

Dstl.

Centre for Defence Enterprise

Building R103

Fermi Avenue

Harwell Oxford

Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX

Email cde@dstl.gov.uk

Telephone +44 (0)30 67704236

Alternative number +44 (0)30 67704237

HOLLAND

YACHTING GROUP - UNMANNED VESSELS UN LAW OF THE SEA, 12

APRIL 2016

Is an unmanned ship still a ship? Who is the captain? What if it rams your yacht? Time to overhaul the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, says one maritime law expert.

They are called anything from Unmanned Vessels to Autonomous Marine Systems. Guided from shore-based, windowless, air-conditioned computer rooms thousands of miles away crewless vessels promise a bright future. For maritime transporters, ocean explorers and military commanders. But they also raise vexing legal and safety issues for any craft - from oil rigs to cruise ships to superyachts.

Crewless vessels are not pie-in-the-sky events. There are here and making a difference.

ASV Global, a British company, has already supplied “unmanned and autonomous marine systems” to more than 40 customers. AAI Corp. of Hunt Valley, Maryland, has developed an unmanned surface vessel that can send devices into the ocean. In 2014, Rolls-Royce showed off the world’s first remote-controlled cargo ship (photo). The Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN) is doing a research simulating an unmanned ship in an AIS automatic traffic tracking situation.

Unmanned vessels suit a variety of applications. They are used for anything from border surveillance to mine clearance, from ocean floor mapping to maintenance of oil rigs, pipelines and ships. Over the horizon are unmanned craft carrying cargo and people. Can that be done safely and legally? Is a ship without a captain and crew still a ship? What is the responsibility of its flag state? Who pays when a crewless ship rams an oil rig, a marina or your yacht? What are the liabilities if a superyacht owner opts for an unmanned tender to transport crew, guests and supplies?

Many people are looking into the technological side of unmanned ships. But of the few who explore the legal aspects, none is more diligent than Eric van Hooydonk. The Belgian maritime law expert and lecturer foresees “necessary and undoubtedly extensive” changes in maritime laws. With “the possibility of the commercial breakthrough of unmanned merchant shipping,” now is a good moment to overhaul the basic concepts of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, says Van Hooydonk.

Over the centuries, maritime traffic and trade have embraced new developments rather well. The status of the master and the pilot, the charter party, the bill of lading, liability in collisions, salvage, general average, limitation of liability, marine insurance, the arrest of ships and so on are notions that have all survived intact as seafarers graduated from sail to steam to diesel to nuclear propulsion.

At a workshop at the 2015 Europort, a 3-day gathering of 30,000 shipping professionals in Rotterdam, Van Hooydonk spoke about the legal challenges related to phantom ships. Here is some of his thinking on those issues and the questions they raise:

* Unmanned transport shifts the human factor _ which accounts for 80% of all marine casualties _ to shore-based controllers reading data from onboard sensors. “Safe autonomous operation will ultimately depend on the satisfactory operation of on-board equipment (and) connections with shore stations.”

* Curiously, international maritime law does not define what a ship is. So it can be safely assumed the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea will regard crewless as ships. But will it regard a shore-based controller of an unmanned ship as its ‘master’ under the Law of the Sea?

* What jurisdiction does a flag state have if the owner of an unmanned ship is not established in that state? When the ship never calls on ports of that state? And is run by an anonymous operator at a distant desk in a faraway country? Or from the cloud?”

* Must flag states ensure that unmanned vessels carry on-board documents? Can they order those vessels to render aid at sea? Can a drone vessel give hot pursuit of a foreign vessel? What if someone hacks the

computers on an unmanned ship? Is it then a pirate ship? “An exhaustive critical screening of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea would indeed be very welcome at that juncture,” says Van Hooydonk.

& Unmanned ships lack onboard captains. So who commands the ship? Who represents the owners? “These days,” says Van Hooydonk, “many merchant ships and leisure craft are already equipped with automated navigational systems and auto-steering devices.” But can that gear simply be moved ashore?

* Should there not be an official record of who the shore-based vessel controller is? Voyage data recorders will have to be upgraded to reflect his or her actions. And should they also not record the date and time, a ship’s position, speed, heading, echo sounder depth data, rudder order and response, engine and thruster order and response, hull openings status, accelerations and hull stresses, wind speed and direction and AIS data?

* How does an unmanned vessel meet the requirement that “the captain must be personally present on the bridge upon entering and leaving ports?” New rules may become necessary “to organize dealings between port traffic management and shore-based vessel controllers,” says Van Hooydonk.

HISWA Holland Yachting Group

Tel: +31 20 705 1404

Email: info@hollandyachtinggroup.com

WASHINGTON

POST APRIL

8 2016

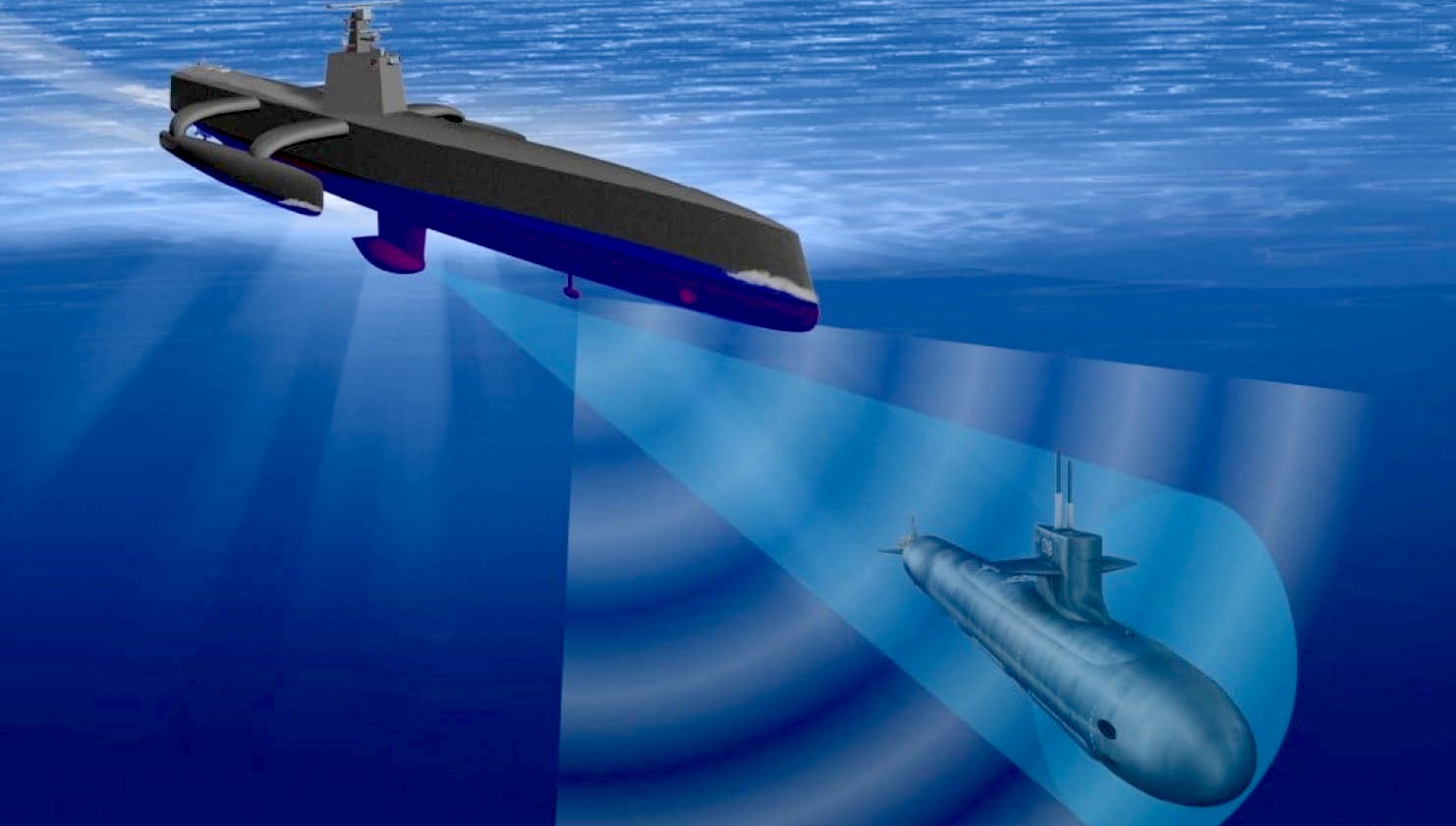

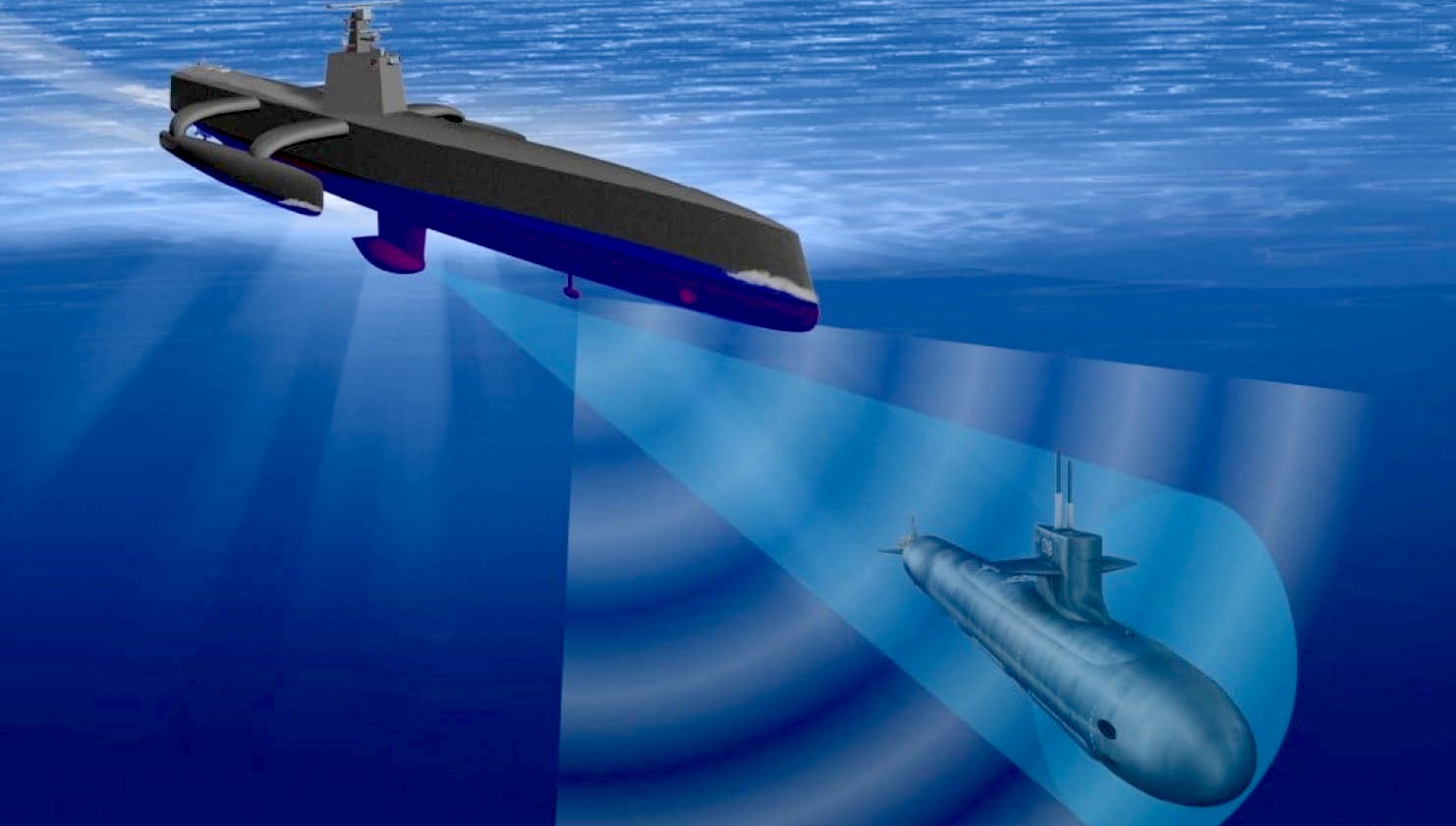

As the Pentagon prepares to face enemies ranging from rival nations to drug smugglers, it’s introducing something new: A 130-foot drone sea craft that could hunt for

submarines and

mines at sea.

Senior defense officials christened Thursday a 130-foot unmanned trimaran in Portland, Ore. The oddly shaped ship is called Sea Hunter and is the centerpiece of the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV) program developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The christening marks a new step for the program, which enters testing this summer off the coast of San Diego and is managed jointly with the Office of Naval Research. If all goes well, the vessel could become part of the Navy in 2018, defense officials said.

The ship’s allure is in its independence. The Pentagon envisions it being able to travel thousands of miles at a time on its own, undertaking missions up to a month long with minimal interaction with humans. Defense officials say it is able to avoid crashing into other ships through advanced software and hardware that form automated “lookouts.” It will be required to meet International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, known in the maritime world as COLREGS.

The ship also can be operated remotely, similar to other drones in the Pentagon’s fleet of unmanned aircraft, ships and submarines. They also could eventually be operated in

fleets, giving the Defense Department an inexpensive way to boost maritime security.

The Sea Hunter test vessel was built by Leidos, a defense and engineering company with headquarters in Reston, Va. It announced last year that a smaller, 42-foot prototype had completed its first self-guided voyage between Gulfport and Pascagoula, Miss. The Sea Hunter was built in Oregon and completed early testing there in the Columbia River.

TULANE

MARITIME JOURNAL APRIL 8 2016 - LAW IN THE NEWS AS DARPA

LAUNCHES AUTONOMOUS VESSEL

Yesterday, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a sub-agency within the Department of Defense, christened an unmanned, automated vessel designed for use by the Navy.

This 130 foot “ACTUV prototype vessel” is capable of traveling thousands of miles without a crew.

Although Navy sailors will control the ACTUV’s mission and have the option of full control of the vessel if need be, the ACTUV is capable of self-navigation.

DARPA will begin “open-water testing” [of ACTUV] . . . conducted jointly with the Office of Naval Research (ONR).”

The thought of unmanned, self-navigated vessels roaming the world’s oceans may raise legal and policy concerns for some. However, DARPA asserts that

“through at-sea testing on a surrogate vessel, ACTUV’s autonomy suite has proven capable of operating the ship in compliance with maritime laws and conventions for safe

navigation - including International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, or COLREGS.”

For a detailed description and analysis of the legal pool that the ACTUV will inevitably be dipping in to, please see Ghost Ships: Why the Law Should Embrace Unmanned Vessel Technology by our very own Paul W. Pritchett (member, Volume 39).

Mr. Pritchett discusses the maritime issues raised by the advent of unmanned vessels including: piracy, collision/navigation rules, cargo damage, and more.

To view Mr. Pritchett’s Comment in full, please use the following links: WestLaw, LexisNexis, HeinOnline. To order a physical copy of Volume 40:1,

click

here.

MUNIN

The

Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks (MUNIN) – is a collaborative research project, co-funded by the European Commissions under its Seventh Framework Programme. MUNIN aims to develop and verify a concept for an autonomous ship, which is defined as a vessel primarily guided by automated on-board decision systems but controlled by a remote operator in a shore side control station.

Maritime transport within the EU faces challenges such as significant increases in transport volumes, growing environmental requirements and a shortage of seafarers in the future. The concept of the autonomous ship brings along the potential to overcome these challenges. It allows for more efficient and competitive ship operation and increases in the environmental performance of vessels. Furthermore the shore based approach offers “seafaring” the possibility to become more socially sustainable by reducing the time seafarers spend away from their families.

On the 10th and 11th of June the project partners and more than 50 guests met at the final event of the research project MUNIN, led by Fraunhofer CML. After nearly three years of research in the draught of the autonomous ship the work concluded at the end of August. For general information about the project and its results, download the MUNIN Final Brochure.

ROLLS

ROYCE, MARCH 23 2016

Rolls-Royce

presents a vision of a future land-based control centre in which a small

crew of 7 to 14 people monitor and control a fleet of remote controlled

and autonomous vessels across the world. The crew uses interactive smart

screens, voice recognition systems, holograms and surveillance drones to

monitor what is happening both on board and around the ship.

TULANE

MARITIME JOURNAL February 27, 2016 - Ghost Ships: Why the Law Should Embrace Unmanned Vessel Technology

Recent years have seen rapid advancement in the development and use of unmanned autonomous and semiautonomous vehicle technology, colloquially known as drones. Initial development of the technology was driven largely by military applications, but it is now being used more and more in the civilian world. Not surprisingly, one of the first civilian applications of this technology occurred in the maritime industry with the advent of unmanned, underwater vehicles. However, until recently, advancements in unmanned vehicle technology have not reached the water’s surface.

In the past few years, there has been an explosion in the discussion, design, and construction of maritime unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). The term “USV” is meant to capture unmanned vessels that operate on the surface of the water and

navigate by remote control, autonomous means, or a hybrid of the two. Since 2010, no less than eight teams have attempted to complete an intercontinental voyage with a USV. In 2012, a USV named PAPA MAU journeyed across the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco to Bundaberg, Queensland, Australia, a distance of nearly nine thousand nautical miles. While most of these attempts have been academic in nature, other organizations are looking to commercialize the technology.

Currently, there are several companies that advertise complete USV systems for use in various security, oil and gas, survey, and scientific applications. While these USVs are all smaller vessels, generally no larger than the average pleasure boat, some experts have started to suggest that eventually the cargo industry could adopt USVs as the primary method of transporting goods. For example, the Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks (MUNIN) project, which is partially funded by the European Union, is working toward “the realization of the vision of autonomous and unmanned vessels by developing and verifying a concept for the autonomous ship.” Similarly, Rolls-Royce’s Blue Ocean development team has created a concept for a fully autonomous container vessel and theorized that “[t]hey might be deployed in regions such as the Baltic Sea within a decade.”

by Paul W. Pritchett

REFERENCES

& LINKS

http://www.autonomousshipsymposium.com/en/

http://www.hollandyachtinggroup.com/news/newsfeed/unmanned-vessels-time-to-adapt-un-law-of-the-sea

http://www.bmtargoss.com/

http://polarisconsulting.co.uk/

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/maritime-autonomous-navigation-in-gps-limited-environments

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/18366503.2016.1229244?journalCode=ramo20

http://www.tulanemaritimejournal.org/ghost-ships-why-the-law-should-embrace-unmanned-vessel-technology/

http://www.tulanemaritimejournal.org/maritime-law-in-the-news-darpa-christens-unmanned-autonomous-vessel/

http://www.unmanned-ship.org/munin/

http://asiamaritime.net/legal-questions-around-unmanned-workboats/

http://www.maritimejournal.com/news101/insurance,-legal-and-finance/legal-questions-around-unmanned-workboats

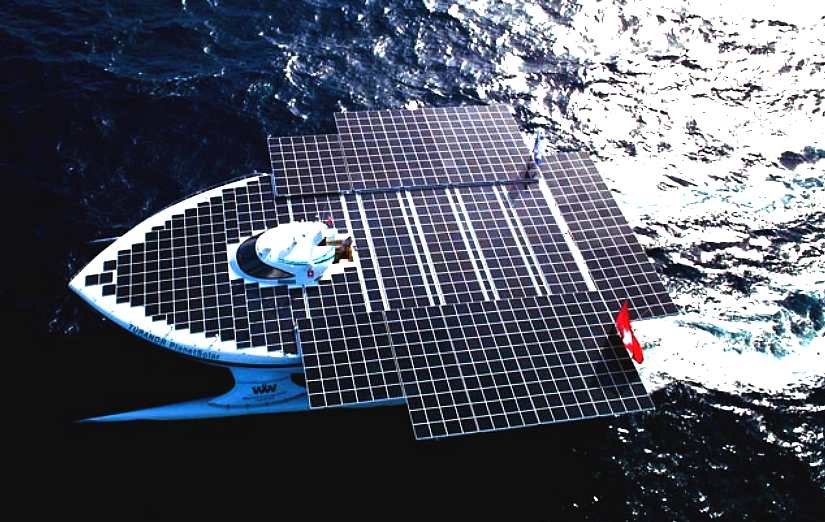

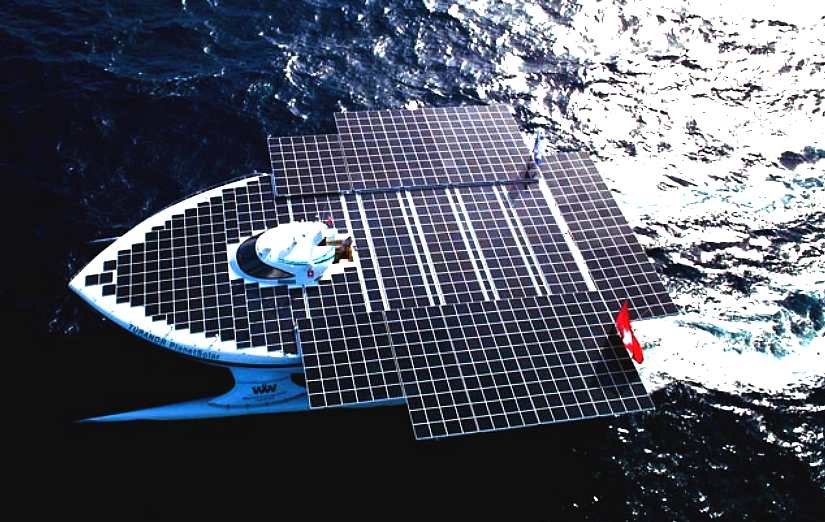

The

biggest and fastest solar boat as of September 2013. The fastest

Atlantic solar boat

crossing took just 22 days to get from the Canary Islands to St. Martins

in the Caribbean.

|