|

THE GLOBAL OCEAN COMMISSION

|

||||||

|

THE OCEAN IS OUR FRIEND, BUT WE ARE NO FRIEND TO THE OCEAN - Why is that? We need fish for food that are toxin free, yet we flood plastic waste and other pollutants into the oceans. Nobody is prosecuted for doing that and there is no fund to clean up the waste - locally or internationally. What are we like! Fortunately, we now have a group of hard hitters, the new kids on the block - and judging from the years of accumulated experience - you don't want to mess with these guys.

The GOC has a huge job ahead of them - and a limited time in which to act - if they are to ensure that the fish stocks we need to sustain us are both plentiful and poison free. It's a tough and dangerous job where fishermen will naturally want to earn as much as possible in a short time span, to offset the high cost of boats, nets and diesel fuel. We should then be sympathetic when seeking to limit catches, giving as much assistance as we can to these brave navigators - to prevent erroneous prosecutions. At the same time, fuel subsidies should be cut to give the privateers a chance to compete - and most of all we need to concentrate on blue growth - so that there are more fish for our fishermen to catch. Now is the time for action .......

THE

GLOBAL OCEAN COMMISSION & INTERNATIONAL RESCUE

The Global Ocean Commission originated as an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, in partnership with Somerville College at the University of Oxford, Adessium Foundation and Oceans 5. It is supported by Pew, Adessium Foundation, Oceans 5 and The Swire Group Charitable Trust, but is independent of all. It is hosted by Somerville College.

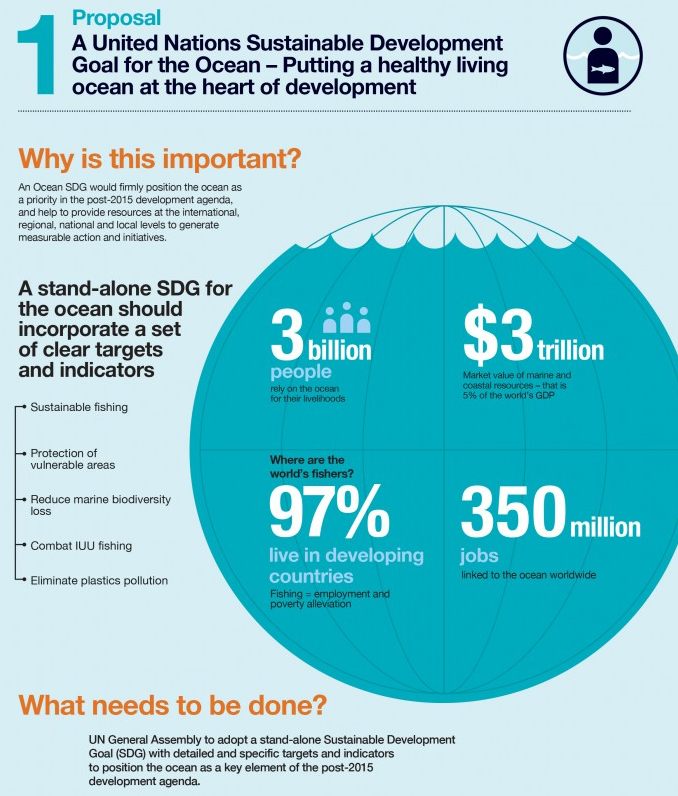

The Commission is working towards reversing degradation of the ocean and restoring it to full health and productivity. Its focus is on the high seas, the areas that lie outside the jurisdiction of individual governments.

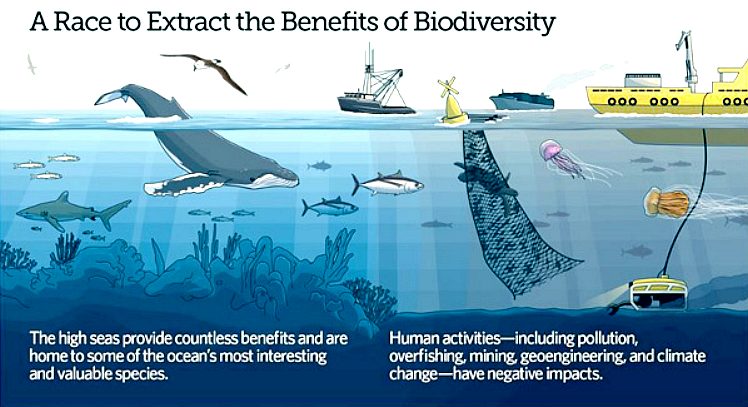

The high seas constitute 45% of the Earth’s surface. According to research reviewed by the Commission, this major proportion of the global ocean is under severe and increasing pressure from over-fishing, damage to important habitat, climate change and ocean acidification. The Commission comprises senior political figures, business leaders and development specialists, and deliberates with a diverse group of constituencies. These include existing ocean users, scientists, economists, business leaders and trade unions.

FISH RESPONSIBLY - Global Ocean Commissioners at the 2013 launch. From left: David Miliband, Obiageli 'Oby' Ezekwesili, Jose Maria Figueres

The Commission will publish its final recommendations in early 2014, shortly before the United Nations General Assembly begins discussions on protecting high seas biodiversity. The Commission’s report will consist of proposals improve the system of governance, thus ending high seas overfishing, stopping the loss of habitat and biodiversity, and improving monitoring and compliance.

The Global Ocean Commission Tel: +44 (0) 1865 280747

THE CO-CHAIRS

CO CHAIR - José María Figueres was President of Costa Rica from 1994 to 1998. Since leaving government, Mr Figueres has served on numerous other boards. Mr Figueres graduated in engineering from the United States Military Academy (West Point). He holds a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard University.

CO CHAIR - Trevor Manuel was one of South Africa’s longest serving Ministers of Finance, and is now Minister in the Presidency and head of the National Planning Commission. After South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, Mr Manuel was appointed Minister for Trade and Industry. Two years later he became Minister of Finance. Trevor Manuel actively opposed apartheid policies for many years, and became head of the African National Congress’s Department of Economic Planning prior to the 1994 election. He was a member of the ANC’s National Executive Committee from 1991 to 2012. Mr Manuel has chaired the International Monetary Fund’s Development Committee, served as Special Envoy for Development Finance for UN Secretaries-General Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-Moon, and served on the Commission for Africa and the task team on Global Public Goods. In 2011 he became a Co-chair of the Transitional Committee of the Green Climate Fund, a UN fund to help poorer nations combat and adapt to climate change. Mr Manuel has received numerous honorary doctorates and awards.

CO CHAIR - David Miliband is President and CEO of the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and a former UK Foreign Secretary. Founded by Albert Einstein, the IRC is a charity that works in more than 40 countries helping refugees and victims of conflict and disaster. Mr Miliband joined the IRC in September 2013 after 12 years as a Member of the British Parliament. His first government post came in 2002 when he was appointed Minister for Schools. As Secretary of State for the Environment from 2006 to 2007, he pioneered the world's first legally binding bill to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As Foreign Secretary from 2007 to 2010, he oversaw creation of a marine reserve around the Chagos Islands, which remains the world's biggest reserve where no commercial fishing is permitted.

WORLD

OCEAN DAY MESSAGE, JUNE 8 2015 - Oceans are an essential component of the Earth's ecosystem, and healthy oceans are critical to sustaining a healthy planet. Two out of every five people live relatively close to a shore, and three out of seven depend on marine and coastal resources to survive. Our oceans regulate the climate and process nutrients through natural cycles while providing a wide range of services, including natural resources, food and jobs that benefit billions of people.

UN

CONCERNS ON MARINE LITTER - In the Rio+20 outcome document, marine litter/debris is considered as one of the major concerns as it negatively affects the health of oceans and marine biodiversity, therefore it calls for actions to achieve significant reductions in marine debris by

2025 to prevent harm to the coastal and marine environment (paragraph 163 of The Future We Want). In The Oceans Compact which was launched during the Yeosu Expo 2012, UN Secretary General

Ban Ki-moon further calls upon all countries to set relevant national targets for nutrients, marine debris and waste water to protect people and improve the health of the oceans.

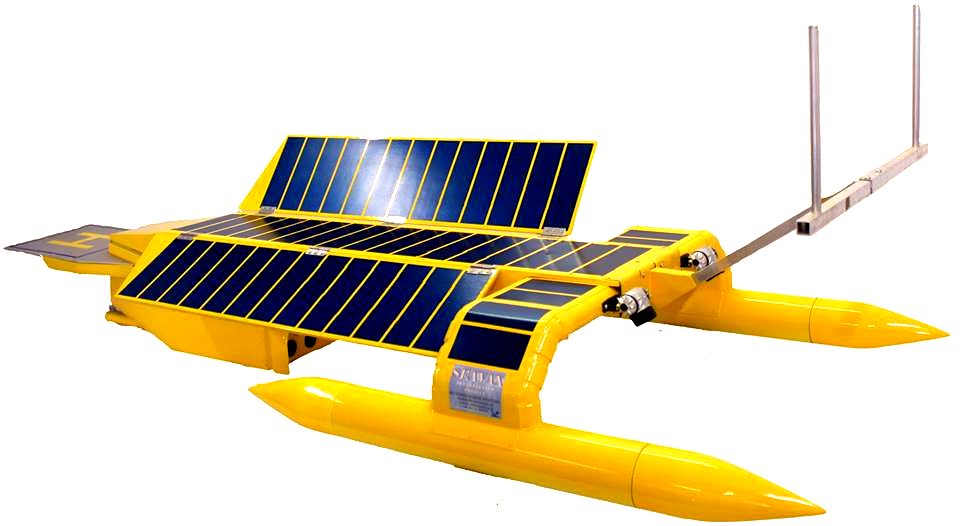

As part of the drive to clean up our oceans, we hope that projects to target plastics that do get into the oceans, may receive recognition and/or support. One such project is the Cleaner Oceans Project with plans to develop ocean scrubbers based on the 'proof of concept' boat seen above. Contact BMS for more information.

HRH the Prince of Wales speaking at a Global Ocean Commission event in Washington DC in March of 2015. The future King of England has consistently kept a weather eye open to help safeguard the marine environment. Prince Charles also met with President Obama on this visit to the USA. The US President is quoted as saying that climate change is one of the greatest threats to security.

BRIEFING - IMO WELCOME GLOBAL OCEAN COMMISSION REPORT - AUGUST 2014

International Maritime Organization (IMO) Secretary-General Koji Sekimizu has welcomed the recently-published report of the Global Ocean Commission (GOC), From Decline to Recovery: A Rescue Package for the Global Ocean, and its call for enhanced action at all levels to mitigate the threats to the global oceans described in the report.

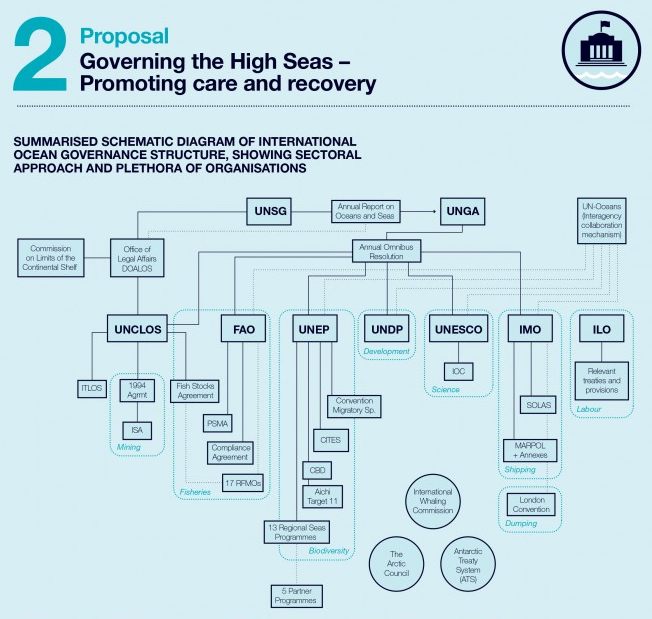

In a letter to the co-chairs of the Global Ocean Commission (Mr. José María Figueres, Mr. Trevor Manuel and Mr. David Miliband), Mr. Sekimizu noted that, as the United Nations specialized agency dedicated to sustainable uses of the world’s oceans through safe, secure, clean ships, IMO plays a key role in advancing the critically important agenda carried forward in the report and has adopted key treaties addressing several of the outlined threats.

Mr. Sekimizu highlighted IMO’s active role in addressing many of the issues raised in the GOC report, noting also that IMO is working actively through several existing coordination mechanisms – such as UN Oceans, the Global Partnership for Oceans, and the Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP) – to ensure that joint efforts are maximized and duplication reduced.

“In my view, thoughtful development of ocean regulations, coupled with early entry into force, effective implementation, stringent compliance oversight and vigorous enforcement of international standards are the best ways to protect and sustain the precious marine environment and its resources. Through the application of these principles, for example, the average number of large

oil spills (>700 tonnes) during the 2000s was just an eighth of that during the 1970s. This dramatic reduction has been due to the combined efforts of IMO, through its Member Governments and the oil/shipping industries to improve safety and

pollution prevention,” Mr. Sekimizu said.

In other examples of IMO’s commitment and ongoing work to address the challenges outlined in the GOC report, Mr. Sekimizu referred to IMO’s work to support sustainable development, including pollution reduction through implementation of the MARPOL Convention and IMO’s other multilateral environmental agreements, in tandem with capacity-building efforts.

With regard to sustainable use of the oceans, particularly fishing, Mr. Sekimizu referred to IMO’s work with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to address illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, as well as the IMO Cape Town agreement of 2012, aimed at addressing fishing vessel safety.

Regarding the need to strengthen the governance of the high seas through promoting care and recovery, Mr. Sekimizu pointed to IMO’s lead role in the development of ecosystem-based management tools applicable to all marine areas and the designation to date of fourteen Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas, and the adoption of various special areas under MARPOL addressing operational discharges from shipping. Furthermore, IMO has established multiple traffic separation schemes and other ship routeing systems in major congested shipping areas in the world.

IMO Secretary General: Koji Sekimizu

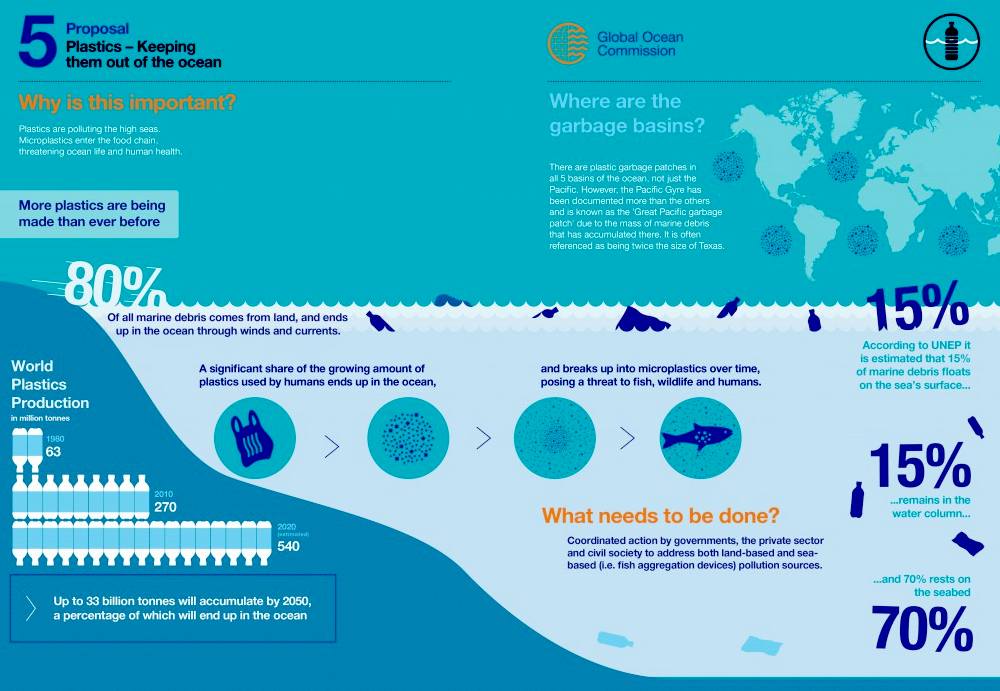

With respect to the report’s Proposal 5 (Plastics – Keeping them out of the Ocean), Annex V of IMO’s

MARPOL treaty prohibits the discharge of plastics from ships. The key issue is effective implementation, Mr. Sekimizu noted.

PROPOSAL 5 - KEEPING PLASTICS OUT OF THE OCEAN

Plastics are a major source of pollution on the high seas and a health threat to humans and the environment. This reflects poor handling and waste management practices on land and requires a combination of political and regulatory action supported by an increase in consumer awareness.

POPE FRANCIS - Refreshingly, Pope Francis embraces the need to tend our gardens is Christian manner, and our duty to do what we can. He is quoted as saying: “If we destroy Creation, Creation will destroy us.” Rémi Parmentier, Trevor Manuel and Simon Reddy are seen here (right) with Cardinal Dominique Mamberti at the Vatican in Rome.

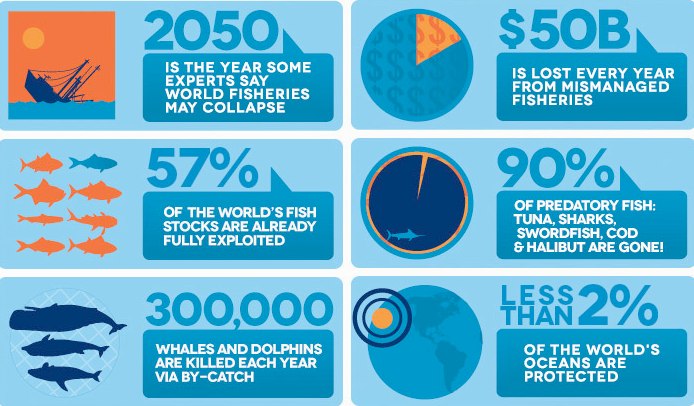

BOUNTIFUL HARVEST - Fishing is an essential activity for sustainable food supply. Over-fishing costs the global economy around $50 billion dollars a year.

Marine life needs to be protected against ocean pollution. Ocean pollution includes plastic, nets and oil spills. Technology with the potential to alleviate such issues should be accelerated as a high priority.

GOM OBJECTIVES

The objective of the Global Ocean Commission is to address

the issues hereis by formulating ‘politically and technically feasible

short, medium, and long-term recommendations.

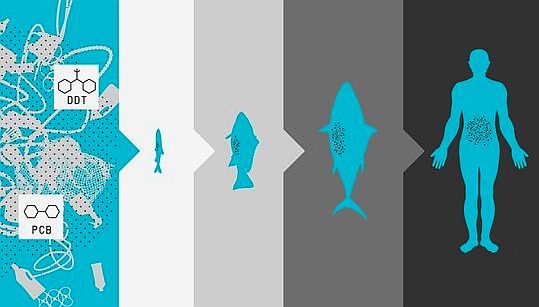

Tons of plastic floating in our oceans is a serious problem we face on this globe, considered to be one of most serious threats to our oceans. 90% of all trash floating on the ocean’s surface is in the form of plastic materials, with 46,000 pieces of plastic per square mile. Plastic does not biodegrade, it photo-degrades with sunlight, breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces. These plastic pieces are eaten by marine life and eventually works it way up the food chain - as per the diagram below.

Plastic is also swept away by ocean currents, landing in swirling vortexes called ocean gyres. The North Pacific Gyre off the coast of California is home to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the largest ocean garbage site in the world. The floating mass of plastic is twice the size of Texas. These floating garbage sites are impossible to fully clean up. Over 100,000 marine mammals and one million seabirds die each year from ingesting or becoming entangled in plastic. Plastic poses a significant threat to the health of sea creatures, both big and small. It takes 500-1000 years for plastic to degrade, threatening both human and ocean health.

GLOBAL OCEAN COMMISSIONERS - A map of the world showing the location of the GOC's commissioners.

THE COMMISSIONERS

TERRAMAR PROJECT - WHO OWNS THE HIGH SEAS ?

For 64 percent of the world’s oceans - the amount that lies beyond national jurisdictions - the answer is that nobody owns the high seas. The high seas, as they’re known, are like the planet’s commons: since they don’t belong to anyone, no nation invests enough in offering them the protection they deserve, even though they constitute 45 percent of the planet’s surface area.

A coalition of NGOs, scientists, and activists called the TerraMar Project aims to reconfigure that relationship with the high seas by offering the opportunity to become a “citizen” of an imaginary aquatic nation.

TERRAMAR FOUNDERS - “45% of our planet is abused, overlooked & not preserved for future generations,” “Just because the high seas are out of sight does not mean they should be out of mind. The TerraMar Project’s number one goal is to change attitudes and governance as it relates to the world’s largest ecosystem.”

The group is now offering passports - complete with unique numbers and a soon to come physical badge - for people to become citizens of the high seas, along with the chance to be “ambassador” for an underwater marine species of your choice. See the BMS passport above. Composed of a mix of NGOs, members of the High Seas Alliance and Save The High Seas, and experts in ocean policy, marine science, and law, the TerraMar network aims to tackle issues plaguing all of our oceans today, not just the high seas, including deep seabed mining, noise pollution, over-fishing, oil spills, and plastic pollution in the ever-growing Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

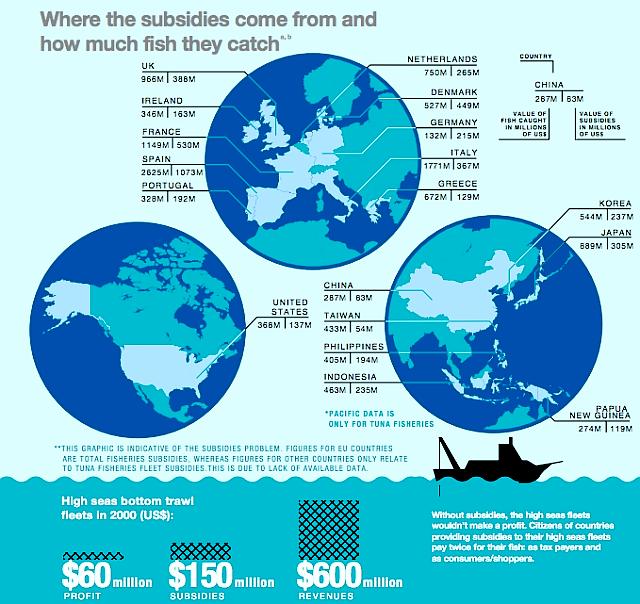

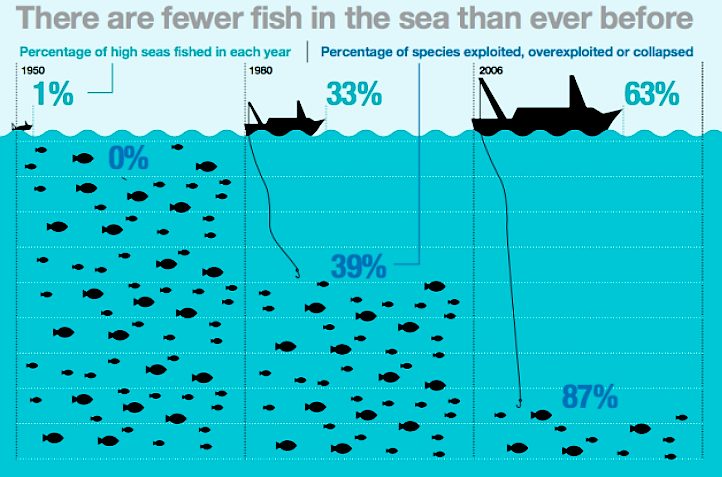

RICH COUNTRIES PAY ZOMBIES $5 BILLION A YEAR IN SUBSIDIES TO PLUNDER THE OCEANS

- Without the subsidies, most of these businesses would fail. So thoroughly have industrial fleets

over-fished the seas that they couldn’t afford the fuel to travel the ever-increasing distance needed to catch the same amount of fish if their governments didn’t lavish public funds upon them.

RICH COUNTRIES PAY ZOMBIES $5 BILLION A YEAR IN SUBSIDIES TO PLUNDER THE OCEANS

- If industrial fleets weren’t subsidized, they’d go out of business. Small-scale fisheries that don’t need enormous amounts of fuel to catch huge hauls of

fish - i.e. the ones using sustainable fishing practices - would then in theory thrive. Many of these fishermen are in poor countries whose governments can’t afford to compete in the industrial looting.

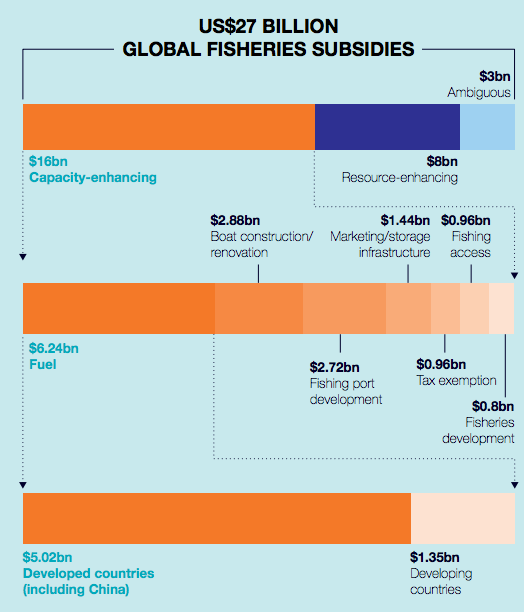

RICH COUNTRIES PAY ZOMBIES $5 BILLION A YEAR IN SUBSIDIES TO PLUNDER THE OCEANS

- Not all subsidies are bad. In fact, subsidies to promote fishery resource conservation and

management - things like stock assessments and stock monitoring - are exactly the kinds of things we should be pressing our governments to foot the bill for. But some $16 billion in subsidies goes exclusively toward making it cheaper to catch more fish. That’s a problem, given that the global deepwater fleet is already 2.5 times bigger than what the GOC says is sustainable to maintain global fish stocks.

PANEL DISCUSSION - Governments tend to be leery of slashing subsidies because of the potential impact on jobs and, hence, politics. For instance, in 2006 Spain upped its fuel subsidy 60% after fishermen blockaded Mediterranean ports to protest oil prices. But the industrial fisheries are actually not huge employers, even within their sector: the GOC reports that the biggest vessels catch 65% of all marine fish, while employing only 4% of fishermen.

Launched in July 2012, the group has taken these unclaimed waters and christened them TerraMar, “the 8th Wonder of the World,” a nation that deserves care and attention. By metaphorically transforming these waters into a tangible country, the founders hope to draw attention and awareness to the world’s neglected ecosystems. Their first step in reaching their goal: Reaching one million active, informed citizens dedicated to fighting for the voiceless depths and the creatures living within them.

EUROPEAN COMMISSIONER FOR ENVIRONMENT, FISHERIES & MARITIME AFFAIRS

Global Ocean Commission co-Chairs David Miliband, Trevor Manuel and José María Figueres wrote to new European Commissioner for Environment, Fisheries and Maritime Affairs, Karmenu Vella, to express support for the EU’s pioneering regulation on illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and to seek a meeting for further exploration and discussion.

The Commission’s specific proposal on ending IUU fishing can be found in its 2014 report, From Decline to Recovery: A Rescue Package for the Global Ocean.

IUU fishing has a devastating impact on marine environments, livelihoods, food security and illegal fishers. The Global Ocean Commission believes that the EU IUU Regulation has tremendous potential for stopping the trade of illegal fish products into the world’s largest seafood market – the EU – and, as a result, contributing to discouraging and eliminating IUU fishing practices around the globe.

Prince Albert II of Monaco is a supporter of the Global Ocean Commission

The Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (also known in short as DG MARE) is the Commission department responsible for the implementation of the Common Fisheries policy and of the Integrated Maritime Policy. With a staff of about 400, led by Director-General Lowri Evans (right) and based in Brussels, DG MARE is made up of 6 Directorates dealing with all aspects of both policies, including among others conservation, control, market measures, structural actions and international relations relating to fisheries. DG MARE reports to Karmenu Vella (left), Commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. Lowri Evans has been Director-General in DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries since 2010. Prior to that she has worked in several policy areas in the European Commission notably Competition and Employment. She started her professional career in audit and accountancy with Deloitte.

Stopping illegal products from entering the EU allows for the creation of a level playing field for EU fishermen who operate in a legal, transparent and fair way and provides a safety net for protecting the supply chains of European processors and retailers.

The Regulation is also a showcase at the international level, demonstrating the influence one key market state can have as it encourages on-the-ground improvements in fisheries governance, monitoring control and surveillance in flag, coastal and port states, and eradicating some of the key IUU fishing hotspots globally.

As a direct outcome of the EU’s IUU yellow-carding (warning) and red-carding (trade restrictions) process, at least four countries – namely Fiji, Panama, Togo, and Vanuatu – have entirely reformed their fisheries policies and laws, introduced more sophisticated and effective vessel monitoring systems, and brought in sanctions for their nationals and vessels involved in IUU fishing. A large number of pre-identified countries have stressed the importance of cooperation and collaboration with the EU in this process, acknowledging its significant role in the global effort to deter IUU fishing.

ABOUT THE COMMISSIONER FOR MARITIME AFFAIRS AND FISHERIES

The Commissioner for Maritime affairs and Fisheries is a member of the European Commission. The portfolio includes policies such as the Common Fisheries Policy, which is largely a competence of the European Union rather than the members. The Union has 66,000 km of coastline and the largest Exclusive Economic Zone in the world, covering 25 million km². They also participate in meetings of the Agriculture and Fisheries Council (Agrifish) configuration of the Council of the European Union. Their governance is thus a model for the world and should send a signal to other fishing nations as to important issues and remedies. Actions speak louder than words.

The Global Ocean Commission at its meeting in Oxford, 21st-23rd November 2013 (left to right) Robert Hill, Paul Martin, Foua Toloa, Yoriko Kawaguchi, Simon Reddy (Executive Secretary), Victor Chu, Andrés Velasco, Obiageli Ezekwesili, Trevor Manuel (Co-chair), Cristina Narbona, David Miliband (Co-chair), John Podesta, Pascal Lamy, José María Figueres (Co-chair), Vladimir Golitsyn, Ratan Tata.

THE

GUARDIAN, 10 FEB 2013

Bluefin tuna is an endangered species as a result of ocean neglect

Deep sea fisheries carry another high cost in loss of coral forests and sponge groves. Life is glacial in the frigid inkiness of the deep, so these habitats have developed over thousands of years, sustained by table scraps sinking from a narrow surface layer where sunlight fuels plant growth. The bottom trawls that are used to catch fish cut down animals that are hundreds or even thousands of years old.

MISSION STATEMENT

RICH COUNTRIES PAY ZOMBIES $5 BILLION A YEAR IN SUBSIDIES TO PLUNDER THE OCEANS

- The industrial fleet that now drags the high seas for fish has a combined engine power 10 times stronger than it did in 1950. Its nets are so huge that they’re sometimes big enough to hold 12 jumbo jets. And it is largely thanks to this all-out assault on high-seas fishing stocks that two-thirds of those stocks

(paywall) are at the brink of collapse - or well past the edge.

RESPONSIBILITIES

CONTACTS

European Commission

LINKS & REFERENCE

The Guardian comment is free 2013 February 10 stop plunder of the high seas Telegraph US-royal-tour-Prince-of-Wales-makes-plea-for-cleaner-oceans Prince-of-Wales-speech-hrh-the-prince-of-wales-event-titled-plastic-the-marine-environment-scaling Daily Mail Charles-horrified-toll-plastic-dumped-sea-Prince-Wales-plea-solve-issue-sake-future-generations The Guardian environment 2015 March 19 Prince-charles-calls-for-end-to-dumping-of-plastic-in-worlds-oceans http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/prince-charles-speaks-dangers-plastic-waste-oceans-29736519 Time environment-prince-charles-oceans National Geographic Prince Charles oceans trash plastic britain Wikipedia Global_Ocean_Commission ITV 2015-03-18 prince-charles-makes-impassioned-plea-for-oceans-clean-up The-terramar-project-become-a-citizen-and-protector-of-the-high-seas National Geographic news 2014 June Global-ocean-commission-report-high-seas-fishing-environment Virgin leadership and advocacy introducing global ocean commission The terramar project daily catch become a citizen and protector of the high seas Wikipedia European_Commissioner_for_Maritime_Affairs_and_Fisheries Reuters 2013 US oceans new global group to clean up National Geographic 2014 global-ocean-commission-report-high-seas-fishing-environment http://www.nowpap.org/ML-on_UN-level.php http://www.unep.org/NewsCentre/default.aspx?DocumentID=26827&ArticleID=35178 http://missionocean.me/ http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/feb/10/stop-plunder-of-the-high-seas http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/02/11/us-oceans-idUSBRE91A00C20130211 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Commissioner_for_Maritime_Affairs_and_Fisheries http://www.virgin.com/unite/leadership-and-advocacy/introducing-global-ocean-commission http://www.scienceifl.com/ocean-plastic-pollution.htm http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/prince-charles-speaks-dangers-plastic-waste-oceans-29736519 http://www.globaloceancommission.org/ http://time.com/3750375/environment-prince-charles-oceans/ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/03/150318-prince-charles-oceans-trash-plastic-britain/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_Ocean_Commission http://www.itv.com/news/2015-03-18/prince-charles-makes-impassioned-plea-for-oceans-clean-up/

ACID OCEANS - ARCTIC - ATLANTIC - BALTIC - BAY BENGAL - BERING - CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST CHINA - ENGLISH CH GULF GUINEA - GULF MEXICO - INDIAN - MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN GULF - SEA JAPAN - STH CHINA PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - UNCLOS

- UNEP

- WWF

|

||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 2015 Bluebird Marine Systems Ltd. The names Bluebird™, Bluefish™, Miss Ocean™, SeaNet™, SeaVax™ and the blue bird and fish in flight logos are trademarks. CONTACTS The color blue is a protected feature of the trademarks.

|