|

THE BUDWEISER ROCKET CAR 1979

|

|

|

STAN BARRETT and HAL NEEDHAM

Sponsored by Budweiser the Budweiser rocket car was built in 1979 with the intention of being the first land vehicle to break the sound barrier in the "Project Speed of Sound". On the 17th December 1979 the vehicle, driven by Stan Barrett, attempted to break the sound barrier and has left a legacy that has been controversial ever since as the final speed of the vehicle has always been disputed. It was believed that the car could exceed the speed of sound but when the vehicle was run no sonic boom was heard.

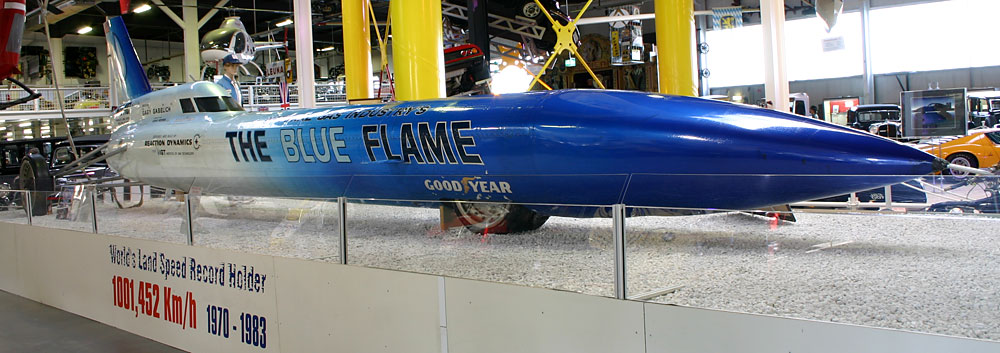

Generally resembling the 1970-era

Blue Flame land speed record holding vehicle in appearance, powered by a hybrid liquid and solid-fuel rocket engine with an extra booster from a sidewinder

missile, that has been claimed as being the first vehicle to have broken the sound barrier on land. The original forerunner to the vehicle was the "SMI Motivator" which was damaged badly enough to require a replacement, which in time was called the "Budweiser

Rocket".

On December 17, 1979 Stan Barrett was strapped into the cockpit of the Budweiser rocket car waiting to make a final run in an attempt to be the first person to drive a land-bound vehicle faster than the speed of sound. Previous trials exposed shortcomings in the basic design of the car. The propulsion system was unable to develop enough power to accelerate the vehicle to a speed high enough to establish an official FIA or FIM sanctioned World Land Speed Record, which at that time stood at 622.

Hal Needham and the team must have reckoned that the rules for land speed racing were in fact obsolete and did not apply to their project. In the team's estimation the general public would not be able to distinguish a peak speed run from an official World Land Speed Record. If the general public accepted their logic and claim of being the first to exceed the sound barrier on land, it could be expected that corporate sponsors would pay a great deal of money for the chance to ride with history. The team in fact, claims a World Land Speed Record, while the Mach 1 event is a purely aerodynamic or atmospheric related phenomenon. Their approach has generated arguments that may rage for quite some time and it is not the author's desire to debate it here. The only issues of critical importance are: did this car reach and exceed Mach 1; and is there evidence that can support such a claim?

The speed was estimated from a radar system at 38 miles per hour - though unfortunately this had been tracking a large truck in the distance, away from the track that the rocket car had used. Some hours after the run the speed (at the vehicle's peak) was calculated at 739.666 miles per hour, ( Mach 1.01 ). This however caused wide skepticism and the speed was never officially recorded.

CONTROVERSY

The first run of the car at

Bonneville Salt Flats showed that the propulsion system was unable to develop enough power to sustain a speed high enough to establish a new official World Land Speed Record. The team decided then that their goal would be to exceed the speed of sound on land, if only briefly, although no official authority would recognize this achievement as a record. The speed of sound is a function of the air temperature and pressure. In other words, the sound barrier is not an absolute speed value, but dependent on air conditions. The speed of sound during Barrett's speed run was 731.9 miles per hour (1,177.9 km/h).

The Blue Flame a the rocket-powered vehicle driven by Gary Gabelich that achieved the world land speed record on Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah on October 23, 1970. The vehicle set the FIA world record for the flying mile at 622.407 mph (1,001.667 km/h) and the flying kilometer at 630.388 mph (1,014.511 km/h).

LINKS

Wikipedia Budweiser_Anheuser-Busch http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Flame_(automobile) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Budweiser_Rocket http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Budweiser_(Anheuser-Busch) http://www.budweiser.com/

|

|

|

This

website is Copyright © 2014 Bluebird Marine Systems

Limited.

The names Bluebird™,

Blueplanet BE3™, Ecostar

DC50™

and the blue bird in flight

|