|

HENRY SEGRAVE - MISS ENGLAND II

|

|

|

On March 29, 1927. Sir Henry O'Neal de Hane Segrave and Gar Wood were standing in front of the latter's winter home on Indian River, Florida. After the War Segrave had told the world that he would build a race car and drive it over the sands of Daytona Beach, Florida, at over two hundred miles an hour. The world thought the War had driven him mad. On that very morning in March, 1927, he had rocketed his Mystery Sunbeam across one measured mile of Daytona sands at 203.79 miles an hour. That was the fastest any human being had ever traveled on land.

Henry Segrave

Tall, slim, handsome, clothed in white tropic knickers tightened with a leather belt about his waist, this young Briton, schooled in danger, was like a bundle of charged steel wire, controlled. At seventeen he was in charge of British machine gunners in France during the War. He left Eton when the War broke out, went to Sandhurst. There he was gazetted a lieutenant in the infantry and rushed to the front.

On May 17, 1915 he was shot in a hand to hand encounter in what was thought to be an abandoned German trench. Segrave was rescued by men of his own battalion and taken back of the lines. For days he was near death. He was sent back to England, convalesced and before long he had joined the British Air Service. He flew to the front April 14, 1916. In less than two months he was gazetted captain and flight commander. He brought down four enemy ships before his own ship was riddled with enemy bullets. His broken body was found at dusk, slumped in a battered cockpit in a tree.

He lived to become technical advisor of the British Air Council. After the War he joined the Sunbeam company. In March, 1927, he took his Mystery Sunbeam to Daytona, Florida, where he set a land speed record that amazed the world.

Having broken the 200 mph barrier, Major Henry Segrave drove the Golden Arrow to a new record speed of 231.446 mph (372.340 kph), again at Daytona Beach, Florida. What made this car unique is that it is on record as the least used car; having been driven a total of 18.74 miles. Segrave was later knighted for his achievements. Sir Henry also attempted to capture the water speed record in his Miss England II when his boat hit a log in the water and capsized, killing Segrave and mechanic Victor Halliwell. (Picture of Segrave & Golden Arrow here.) The competition between Campbell and Segrave brought down the 300 mph barrier.

Segrave, speaking to Gar Wood, said: "There's no reason why Lord Wakefield will not be interested in boats as far as I can see," he said. "We've won the records we wanted on land and in the air. What England wants now is the water speed record and the British International Trophy. I think Lord Wakefield will be interested."

Segrave almost immediately began to experiment, to study. He went to the plant of Hubert Scott-Paine at Southampton, England. Together with Fred Cooper they built Miss England I, powered with the 900-horsepower Napier Lion engine Segrave had used in his Mystery Sunbeam. The boat was twenty-seven and one-half feet long with a seven and one-half foot beam, built of five-skin mahogany.

They made mistakes. Perhaps the greatest mistake they made was building a flexible hull. The hull of a high speed boat must be firm, rugged. At high speeds water becomes similar to a solid; just as air at high speeds in a plane becomes a liquid. No flexible hull could stand the jarring of a boat travelling over a sheet of corrugated glass at eighty miles an hour. That's what a sheet of water becomes at high speed-grooved glass. Segrave found that out in Florida in the Spring of 1929. He shipped his famous racing car, the Golden Arrow, and his Miss England to America on the same boat. With the Golden Arrow he set a new land speed of 231.36 miles an hour at Daytona Beach on March 11, 1929.

After the record Wood went to Segrave and asked the Englishman to show him his boat and give him a demonstration of its performance. Upon looking at the boat when it was out of water Wood saw immediately that the propeller was too large and the bow rudder poorly designed. A test run of the boat proved both these factors to be true.

The Committee at Miami Beach was anxious to have Segrave bring his boat to the annual Regatta and pit it against Wood's Miss America VII. In view of Wood's criticism of his boat, Segrave didn't know what to do, so Wood volunteered to send his crew of mechanics to Daytona Beach to put on a proper rudder and to furnish Segrave with suitable propellers.

After considerable calculation of Segrave's horsepower and hull design Wood ordered three propellers from the Hyde Company and gave them to Segrave. With a new rudder on his boat and with Wood's propellers the Miss England I was a very formidable, competitive boat. That's what Wood wanted. He wanted a good race.

After a successful trial run at Daytona Beach Segrave shipped his boat to Miami Beach. He knew that if he could at least make a showing in this contest he'd have little difficulty getting financial backing from Lord Wakefield for a future Harmsworth boat. He discussed this possibility with Wood and the American sportsman agreed that they should stage a close race. Wood was extremely anxious for Segrave to play an important role in Harmsworth competition.

Segrave had a strong vivid stripe of the dare-devil in him. Before the race he asked Wood for the pole position. Wood said, "That's dangerous, sir. My boat is faster. When I cut in on you you'll have to take my wash." Segrave answered, "I'll take the chance." He was given the pole position. When Wood cut across Segrave's bow the solid spray of his Miss America VII struck Segrave full in the face. For a few desperate seconds Segrave didn't know what had happened.

Miss Alacrity - Henry Segrave

Miss America VII had been in the South for some time and the salt water had eaten away the steering cable unbeknown to the Wood crew. The two boats made a beautiful start. The dark mahogany hull of the Miss America and the pure white hull of the Miss England. Although Miss America VII led the Miss England to the first turn, on making the turn the steering gear cable let go and Miss America was unable to proceed. The news was flashed over the world that at last a British boat had beaten Gar Wood in a championship race. The rules governing this particular event were set up by the American Powerboat Association on what is known as a point system; and all the British boat had to do in the second heat was to finish to gain one more point than the American boat which did not finish the first heat. Segrave finished the second heat and won the race even though Gar Wood lapped him three times.

According to American boat designers, the English made grave mistakes in building Miss England I. In the first place Fred Cooper, designer of the boat, had insisted on both a bow and an aft rudder. Segrave said it helped him to make sharper turns. But Wood told him that an aft rudder is dangerous. And it is. Events at Detroit in 1931 proved it when Kaye Don almost went to his death. Wood uses simply a bow rudder. He makes the sharp turns with his propellers, throttling the inside (buoy) propeller, while the outside propeller is speeded.

Wood also believes that it is dangerous to set the cockpit ahead of the engines. He told Segrave, "I want those engines ahead of me when we crack up. If your hull blows to pieces, what chance have you? Those engines are a wall of steel in front of you." Wood discovered how true this was when his Miss America VI blew up on the St. Clair River the year before this, 1928. But Segrave said, "I've got to see the course ahead of me. I can't see with those engines spitting flames and gases in my face."

The English persisted in this theory. Disaster rode high on the wings of their next boat, Miss England II. Segrave may have escaped death had he been sitting BEHIND the engines at Lake Windermere. I merely say "may have" because nothing is certain in this dangerous business. The fact is that Wood, after almost thirty years of racing, still lives.

Backed by the British Air Ministry, the Rolls-Royce Company, Ltd., had developed a new aircraft engine of 2,000 horsepower. Wakefield went to the Ministry and contracted for the rights to use two of those engines. When the boat was finished it was a seven-ton projectile, powered with two 2,000 horsepower Rolls-Royce engines that spun a tiny twobladed propeller through the water at 12,000 revolutions a minute.

Fred Cooper installed both a bow and an aft rudder. The engines were still behind the cockpit. Segrave and Cooper speeded the boat to completion and took it to Lake Windermere for a try at Gar Wood's world record-92.838 miles an hour, done with Miss America VII on the Detroit River in 1928.

Here was a young man with scarcely two years' knowledge of fast boats already aiming at the world speed record. And doing it with a 4,000 horsepower bomb that hadn't tasted water. That is the character of the Briton.

Miss England II was ready on Friday, June 13, 1930. Segrave, Michael Willcocks, engineer of the boat, and W. Hallwell, of the Rolls Royce Company, Ltd., all dressed in spotless white overalls and special steel lifebelts, stepped into the cockpit. Segrave turned to Willcocks and said, "It's Friday the 13th. I wonder what's going to happen." Two of them were going to their death.

The boat shot out above the measured-mile straightaway where the official timers stood, ready to dash over the measured-mile laid out about in the center of the lake between Lakeside and Ambleside. Segrave was making a few practice spins far out there above the markers. The Miss England II looked like a white ghost, its wings of spray spread wide, its engines droning-a thing of beauty, symmetry, flawless grace. It was perhaps the most beautiful speedboat ever built, its bow and its aft end tapering almost to the thinness of a knife blade.

It cut a great white arc in the water, then it straightened. Segrave was cutting down toward the markers, his steady hand tight on the wheel, his eyes glued to the narrow, glass-flat path before him, his foot pressing the throttle to both engines.

The engines cannoned louder as they approached the first marker. When he crossed, throttles down, the thing was like the mad screaming of 4,000 wounded war horses, agonized and frightened. Miss England II shot across the first mile at 96.41 miles per hour. Two runs must be made across the measured mile; one against wind or current, one with. It came back at 101.11 miles an hour. The average was 98.76 -a new world record.

But this courageous young Briton did not know he had broken the world record. He was not satisfied. He took his craft to the upper end of the course again and brought it back with everything it had. The roar was terrific. The official timers could not clock it this time. It did not complete the mile. It made a sudden turn, the quivering thing shot clear of the water like a white rocket, its engines screaming. Segrave and his two men were pitched like meteors from the cockpit. There was a puff of blue, curling smoke . . . a dive . . . silence.

Ten boats rushed out to the rescue. Segrave himself was picked up by P. F. King, of Windermere, who plunged into the lake after him. He was unconscious. Hallwell drowned. Willcocks was severely injured.

Segrave and Willcocks were rushed to a hospital. Segrave suffered a broken arm, a broken rib and a fractured thigh. He regained consciousness for a few minutes. He turned to Lady Segrave at his bedside and asked, "How are the lads?" meaning his men. And then, "Did we do it?" Lady Segrave told him he had, that he broken the record.

He died in a few moments of lung hemorrhages. The drowned body of Hallwell was found, a pencil clutched in one hand, a pad of paper in the other. He'd evidently been taking tachometer readings. Willcocks recovered.

Probably no one will ever know for sure what sent these men to their death. It may have been the tremendous torque on the tiny propeller. Twenty minutes after the disaster a water-soaked branch of a tree, three inches thick, was picked up several hundred yards from the stern of the boat. That may be the answer. No one knows.

The most likely solution to the riddle is that the detachable step ripped off. The forward plane of Miss England II was built on after the main hull was completed and was not an integral part of the boat in its original design. The reason for this, Segrave explained, was that neither he nor his designers knew for sure what angle the forward plane should be in order to get the best performance and that the structure they applied was made so that it could be moved and changed.

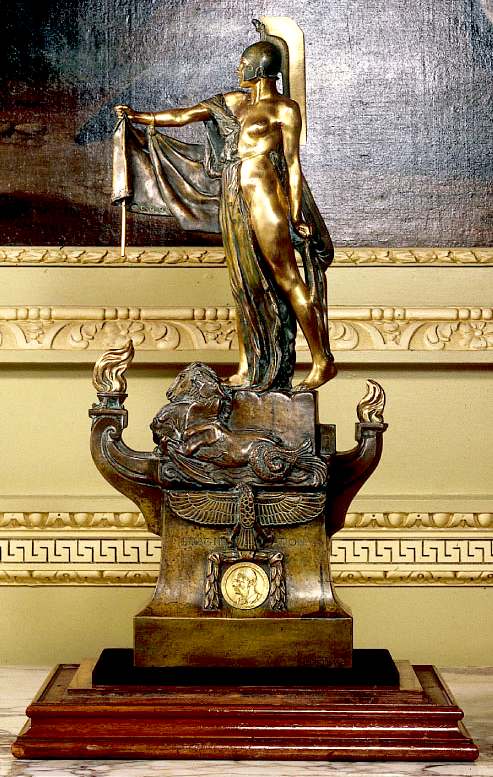

The Segrave Trophy was established in 1930 to commemorate the life of Sir Henry Segrave. A former fighter pilot in World War I, Segrave went on to become Britain's top motor racing driver of his era. He was the first Briton to win a Grand Prix in a British car, winning the French and Spanish Grand's Prix in a Sunbeam. He later went on to set the world land speed record, but was later killed setting the world water speed record. The Seagrave Trophy is awarded annually to a British subject who accomplishes the most outstanding demonstration of transportation by land, air or water.

|

|

|

This website is Copyright © 2014 Bluebird Marine Systems Limited. The names Bluebird™, Bluefish™, Blueplanet BE3, Ecostar DC50™, Utopia Tristar™ and the blue bird and fish in flight logos are trademarks. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged.

|